Published on 28th Mar 2023 –

Updated on 15th Aug 2025

Finding a safe road during an earthquake is very crucial for

civilians.

When snow sweeps across the country, the online world for

education providers take a pretty big hit. It doesn’t seem

obvious at first, why would it?

Safemap navigation

Designing routing systems for earthquakes requires frontend

usability studies and backend algorithm modifications.

Evaluations from subject-matter experts can enhance the design

of both the front-end interface and the back-end algorithm of

urban artificial intelligence (AI). Urban AI applications need

to be trustworthy, responsible, and reliable against

earthquakes, by assisting civilians to identify safe and fast

routes to safe areas or health support stations. However, routes

may become dangerous or obstructed as regular routing

applications may fail to adapt responsively to city destruction

caused by earthquakes.

In everyday scenarios, we rely on routing applications like

Google Maps for navigation, gradually leaning on our spatial

memories as we familiarize ourselves with recommended routes.

However, during earthquakes, these applications may fall

short, lacking optimization to guide civilians to safe routes,

especially when roads are rendered inaccessible by

destruction. In such urgent and stressful earthquake

situations, citizens seek refuge in shelters, hospitals, and

open spaces. Relying on regular routing applications poses

risks to individual navigation in earthquakes, as these

applications are designed to operate under normal conditions,

focusing on the shortest routes without considering the impact

of seismic destruction on the city. Routes can become

impassable due to earthquake-induced damage on city

infrastructure, and thus the risk of following collapses or

aftershocks remains elevated if civilians attempt to traverse

them. A routing system designed to respond to earthquakes can

enhance the disaster resilience of cities and urban areas. In

the field of Urban AI, the integration of both frontend user

experience design and backend algorithm modification can

address the complex challenges faced by cities from studies in

urban science, spatial computation, user experience, and

artificial intelligence. In this context, our research

question is: How can a routing system be designed for

earthquake scenarios that integrate algorithm modification and

user interface design effectively?

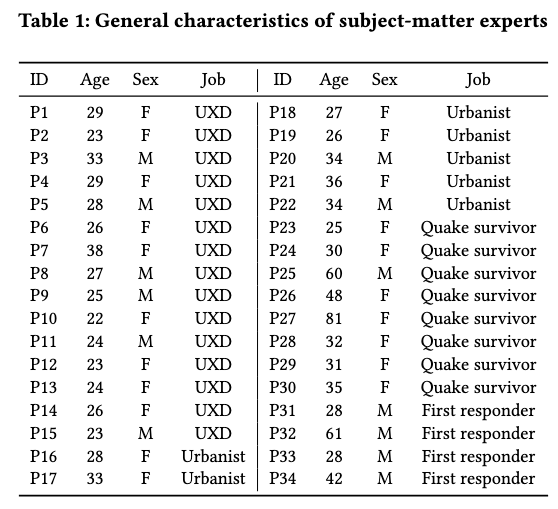

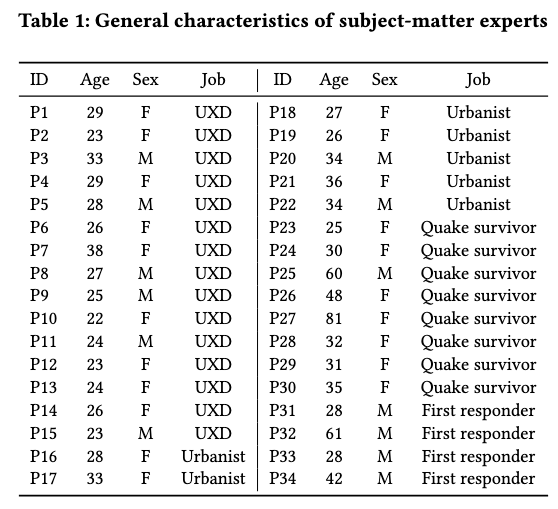

To comprehend the subject of routing systems for earthquakes, it is crucial to involve subject matter experts in the design of such systems. These include urbanists, who analyze the earthquake impact on the city; UX designers, who assess user experience in utilizing mobile routing applications; quake survivors, who offer insights and experiences regarding human behavior and safety during earthquakes; and first responders, who provide perspectives on delivering medical support and emergency rescue to civilians during seismic events. By collaborating with these subject matter experts, we can iteratively refine the design of the routing application, and modify algorithms that are apt for earthquake scenarios.

To comprehend the subject of routing systems for earthquakes, it is crucial to involve subject matter experts in the design of such systems. These include urbanists, who analyze the earthquake impact on the city; UX designers, who assess user experience in utilizing mobile routing applications; quake survivors, who offer insights and experiences regarding human behavior and safety during earthquakes; and first responders, who provide perspectives on delivering medical support and emergency rescue to civilians during seismic events. By collaborating with these subject matter experts, we can iteratively refine the design of the routing application, and modify algorithms that are apt for earthquake scenarios.

Method

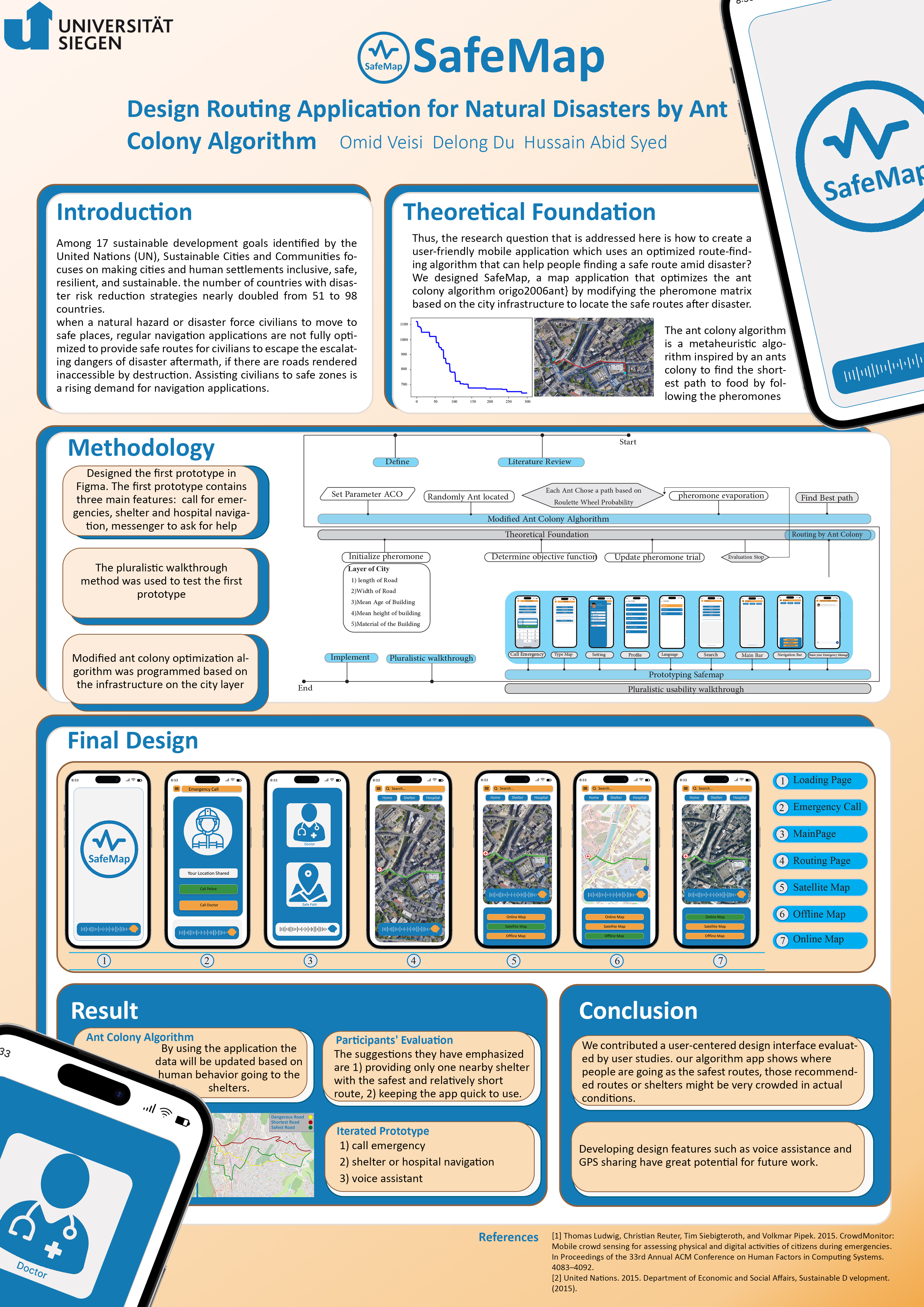

The methodology of this research paper is meticulously

structured to thoroughly delineate the development and

validation process of the proposed Modified A-Star Algorithm

for Routing in Earthquakes. This research endeavour employs a

multi-phased strategy, illustrated in Fig1 , and is anchored

in the principles of research through design.

The first phase of our research involved conducting an extensive pre-study and literature review, enriched by the insights of two professors specializing in urban planning. This foundational step was pivotal in contextualizing our work within the broader realms of urban planning and algorithmic routing. Subsequently, we crafted the inaugural prototype of the SafeMap application, incorporating a refined A-Star algorithm designed to integrate city infrastructure layers. In the event of an earthquake, this application aims to identify the most secure and efficient routes to designated shelters.

The second phrase encompassed user tests aimed at validating the effectiveness and usability of SafeMap. We employed the pluralistic walkthrough technique, engaging 34 participants from diverse areas of expertise, including 15 UX designers, 7 urbanists, 8 quake survivors, and 4 first responders. The invaluable insights provided by these participants were instrumental in refining the application through iterative prototyping. The evaluations concentrated on assessing the user experience, usability, and overall functionality of the system. This phase played a pivotal role in shaping the final design of the application, ensuring its alignment with user needs and experiences.

The third phase was dedicated to expert consultation and refinement of the algorithm across the four identified categories. Initially, collaboration with UX designers, quake survivors, and first responders facilitated the creation of an iterated prototype, grounded in our comprehensive evaluation and spectaculative design. Subsequently, our focus shifted to conducting interviews with professionals in Urbanist and planning, aiming to garner insights into urban resilience and planning. Moreover, engaging in dialogues with specialists allowed us to underscore key components identified by participants, especially those frequently mentioned by quake survivors and first responders. Suggestions for refining the algorithm were developed concurrently, encompassing proposals for compiling a comprehensive road-based dataset, assigning subsequent weights, and integrating safety-related criteria into the routing algorithm. This iterative methodology enabled SafeMap to evolve in alignment with user needs while accommodating the complexities of fluctuating urban landscapes.

To sum up, the research paper utilized a methodical and iterative approach that incorporated feedback from both experts and users to create a routing algorithm that is effective and user-friendly within the SafeMap app. The various phases, including initial algorithm development, consultations with experts, and continuous improvement, played a vital role in shaping the final design of the application. As a result, the app is now capable of testing its assistance to individuals in earthquake drills.

The first phase of our research involved conducting an extensive pre-study and literature review, enriched by the insights of two professors specializing in urban planning. This foundational step was pivotal in contextualizing our work within the broader realms of urban planning and algorithmic routing. Subsequently, we crafted the inaugural prototype of the SafeMap application, incorporating a refined A-Star algorithm designed to integrate city infrastructure layers. In the event of an earthquake, this application aims to identify the most secure and efficient routes to designated shelters.

The second phrase encompassed user tests aimed at validating the effectiveness and usability of SafeMap. We employed the pluralistic walkthrough technique, engaging 34 participants from diverse areas of expertise, including 15 UX designers, 7 urbanists, 8 quake survivors, and 4 first responders. The invaluable insights provided by these participants were instrumental in refining the application through iterative prototyping. The evaluations concentrated on assessing the user experience, usability, and overall functionality of the system. This phase played a pivotal role in shaping the final design of the application, ensuring its alignment with user needs and experiences.

The third phase was dedicated to expert consultation and refinement of the algorithm across the four identified categories. Initially, collaboration with UX designers, quake survivors, and first responders facilitated the creation of an iterated prototype, grounded in our comprehensive evaluation and spectaculative design. Subsequently, our focus shifted to conducting interviews with professionals in Urbanist and planning, aiming to garner insights into urban resilience and planning. Moreover, engaging in dialogues with specialists allowed us to underscore key components identified by participants, especially those frequently mentioned by quake survivors and first responders. Suggestions for refining the algorithm were developed concurrently, encompassing proposals for compiling a comprehensive road-based dataset, assigning subsequent weights, and integrating safety-related criteria into the routing algorithm. This iterative methodology enabled SafeMap to evolve in alignment with user needs while accommodating the complexities of fluctuating urban landscapes.

To sum up, the research paper utilized a methodical and iterative approach that incorporated feedback from both experts and users to create a routing algorithm that is effective and user-friendly within the SafeMap app. The various phases, including initial algorithm development, consultations with experts, and continuous improvement, played a vital role in shaping the final design of the application. As a result, the app is now capable of testing its assistance to individuals in earthquake drills.

Fig 1. Research Framework to develop Safemap application

Subject-Matter Experts for Earthquake

Given the intricate interplay between humans and cities during

earthquakes, we recruited representatives from four categories

of subject-matter experts to assess and refine our design. These

experts comprised 15 UX Designers (UXD), 7 Urban Planners, 8

quake survivors, and 4 First Responders. Within simulated

earthquake scenarios, we engaged quake survivors to test our

app, UX designers to refine the app’s design, urban planners to

evaluate modifications to the algorithm, and first responders to

assess the app’s utility in earthquake rescue scenarios. This

multifaceted approach ensured a comprehensive evaluation and

refinement of the app, addressing the diverse needs and insights

arising from different perspectives and experiences related to

earthquake response and urban navigation. The subject-matter

experts are listed in Table 1.

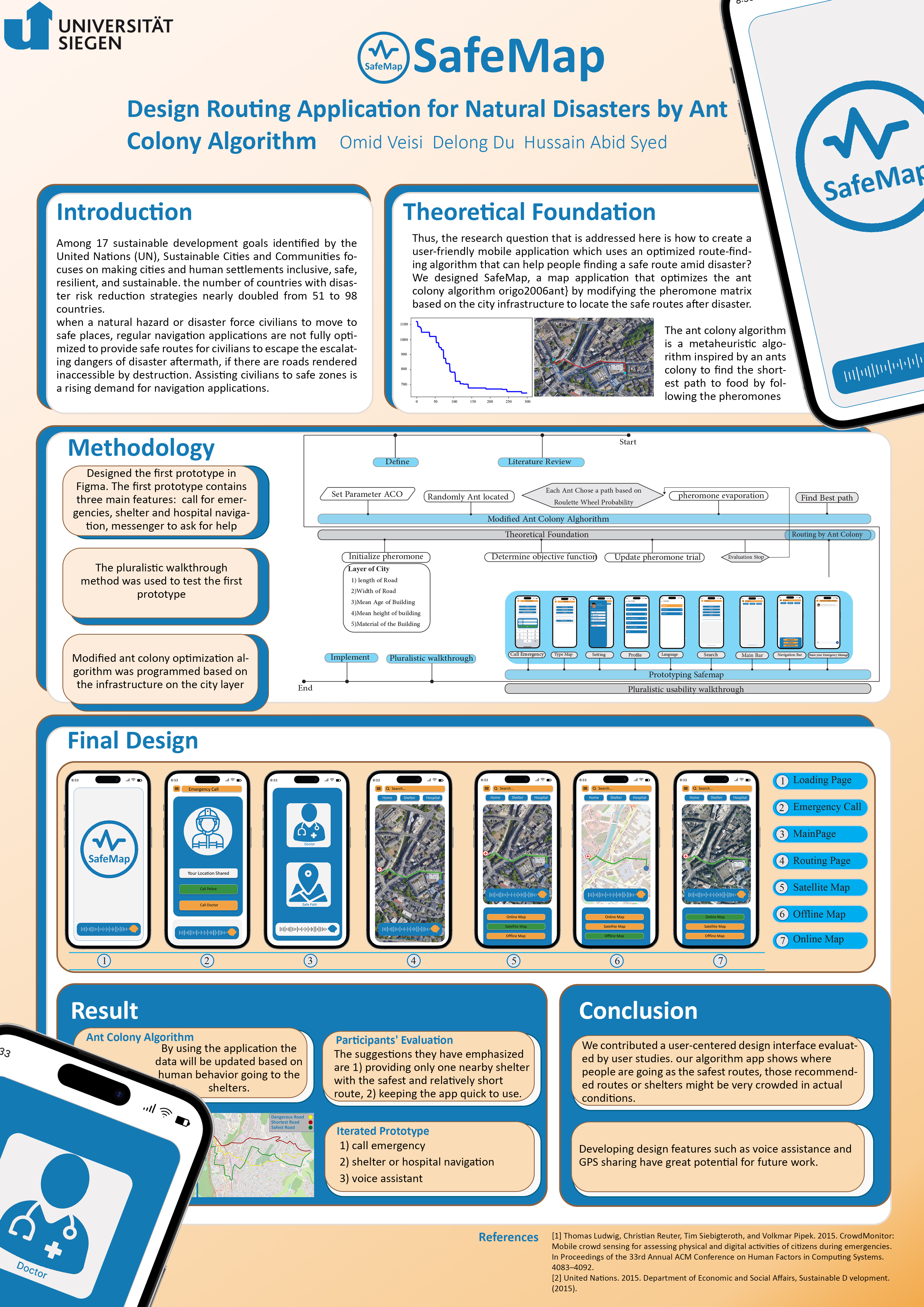

Prototyping Urban AI Navigation Application For Earthquakes

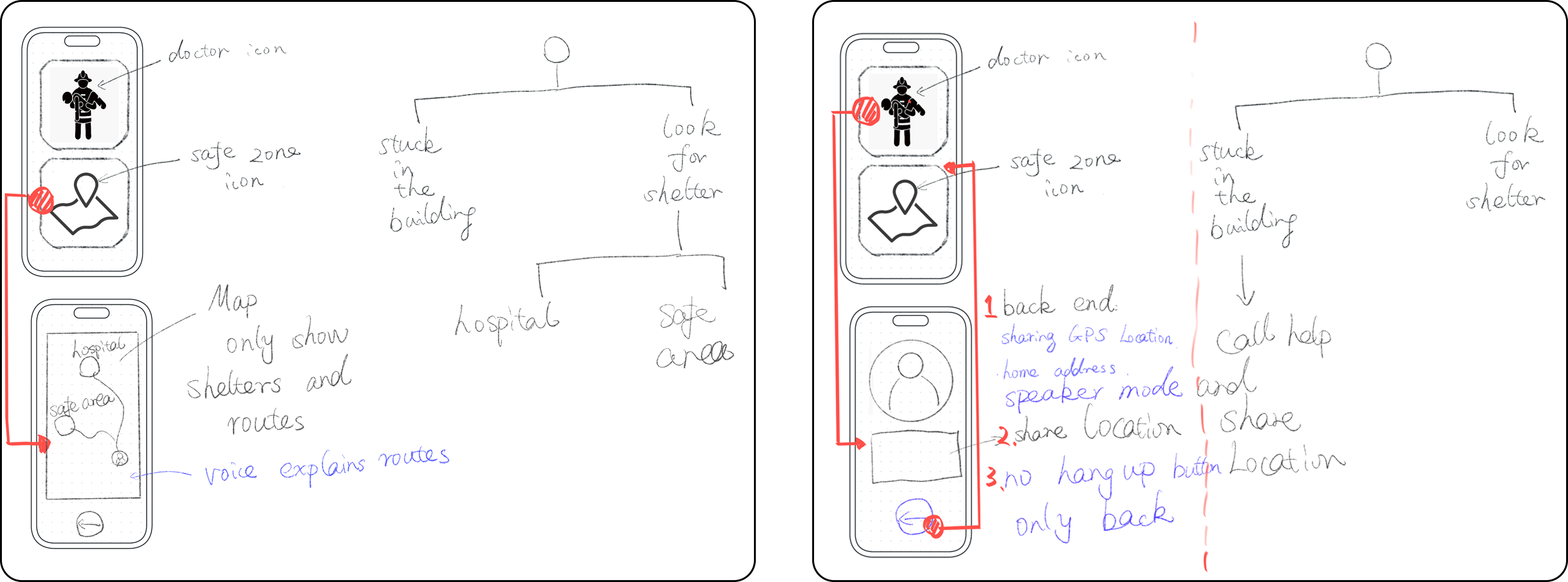

The initial prototype was designed using Figma and encompasses

three principal features: 1) a call function for emergencies,

facilitating contact with first responders services for

medicinal and rescue supports; 2) navigation to shelters and

hospitals; and 3) a messenger feature to request assistance.

In the process of creating the mock-up for nearby shelters, we

utilized Google Maps to search for "shelters near our

researched location." However, the search yielded no results

for our specified location, prompting us to search for

hospitals instead. This scenario exemplifies the limitations

of conventional navigation applications like Google Maps in

providing assistance during earthquake situations.

Fig 2. Wire framing for prototyping version

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation and refinement of the

application, a multifaceted approach was employed, involving

representatives from four categories of subject-matter

experts: UX Designers, urbanists, quake survivors, and first

responders. The appropriation phase involved semi-structured

interviews and observation methods to gain insights into the

user's interaction with the system. During the observation

sessions, videos capturing user interactions, the screen of

the primary Android tablet, and the interviewer's voice were

recorded. This method allowed for a detailed examination of

the interaction between the users and the system, enabling the

identification and understanding of user complaints and the

reasons behind them. The usability test approach was grounded

in the Think-Aloud Protocol technique of usability testing

\cite{van1994think}. Participants were required to vocalize

their cognitive processes while interacting with the program,

accomplishing specific activities designed to assess various

aspects of the application. Researchers provided prompts and

questions to encourage participants to verbalize their

thoughts and feedback on the system continuously. The

activities were presented in print or on a laptop, and

participants were encouraged to express their opinions

verbally as they navigated through them. Researchers monitored

the sessions closely, intervening as necessary to address

technical difficulties and ensure the progression of the test.

Participants were allowed to explore the program freely, with

no imposed order of completing activities, allowing for an

intuitive interaction with the system. This meticulous process

of appropriation and evaluation, involving diverse

subject-matter experts, was pivotal in enhancing the app's

usability and effectiveness in real-world earthquake response

and urban navigation scenarios.

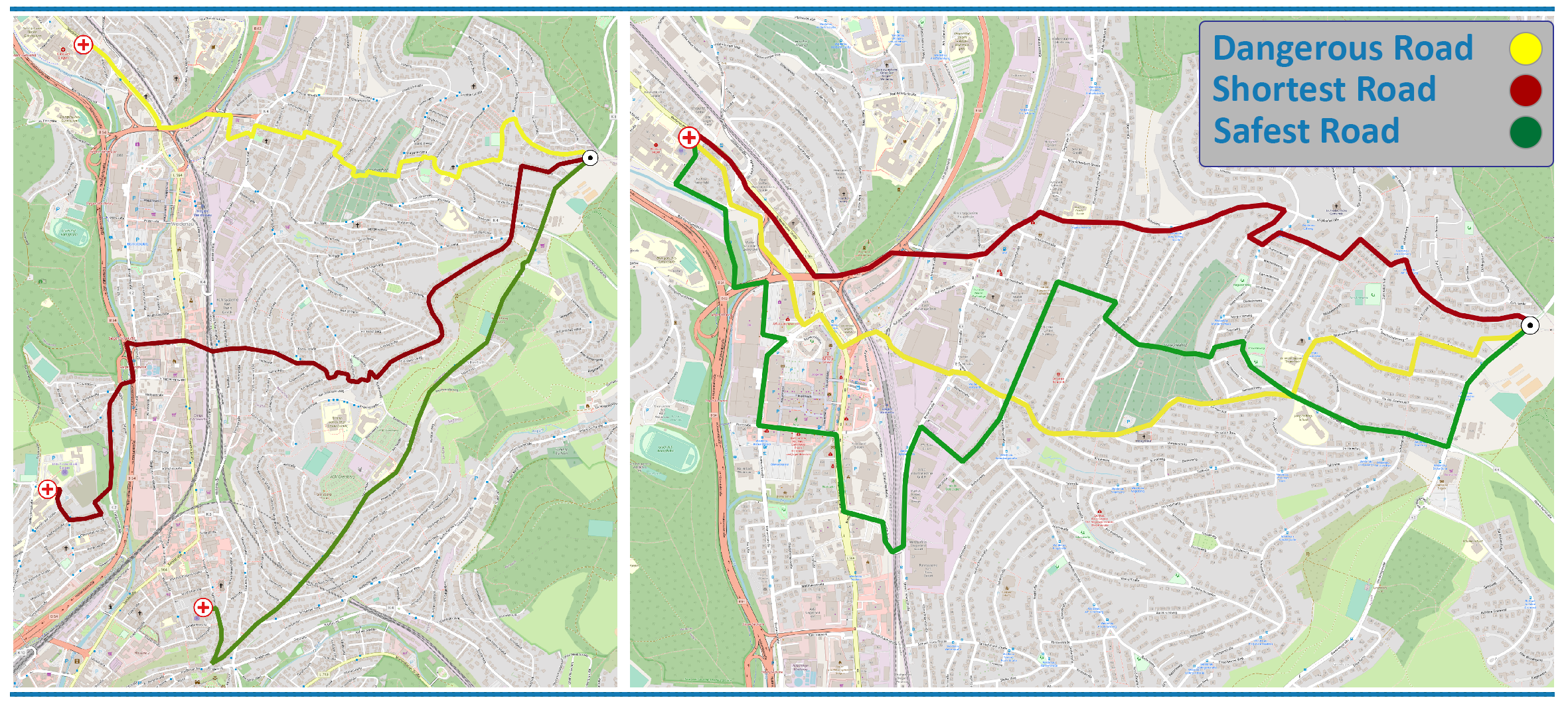

During the study, the facilitator presents participants with the user interface images and asks participants to think aloud about what interaction they would do to achieve specific tasks. After the participants have given their answers on how they would perform the interaction to achieve their tasks, the facilitators provide further information to participants to invite discussion. In order to gather user data to test our algorithm and this first prototype, we collected users' preferences on path choices. We edited three routes in Google Maps to ask our participants which path they would choose. Each route has different safety levels, shown as red, yellow, and green. Green is the safest. We gathered data about 1) participants' path choice before and after additional information about city infrastructures affected by hazards, 2) heuristic strategy about participants' judgment on what they consider safe to reflect on city infrastructures, and 3) participants' suggestions for prototype iteration. During the Pluralistic walkthrough, a set of questions were answered by participants.

During the study, the facilitator presents participants with the user interface images and asks participants to think aloud about what interaction they would do to achieve specific tasks. After the participants have given their answers on how they would perform the interaction to achieve their tasks, the facilitators provide further information to participants to invite discussion. In order to gather user data to test our algorithm and this first prototype, we collected users' preferences on path choices. We edited three routes in Google Maps to ask our participants which path they would choose. Each route has different safety levels, shown as red, yellow, and green. Green is the safest. We gathered data about 1) participants' path choice before and after additional information about city infrastructures affected by hazards, 2) heuristic strategy about participants' judgment on what they consider safe to reflect on city infrastructures, and 3) participants' suggestions for prototype iteration. During the Pluralistic walkthrough, a set of questions were answered by participants.

Fig 3. Wire framing for prototyping version

Our primary findings are categorized into two main components:

User Experience Design and Algorithm Modification.

The first component, User Experience Design, involves insights related to the design of the navigation user interface. It emphasizes the imperative nature of ensuring the rapid usability of the earthquake navigation app, a crucial element given the heightened tension and time sensitivity users experience during an earthquake. The prompt usability of the app is pivotal to guarantee that the app’s response and feedback are immediate and efficient, necessitating a design free of complicated operations. Additionally, our expert user research reveals a cautious view regarding the integration of augmented reality and voice assistant technologies during earthquakes, due to the limited field of view and over-immersion, making users becomes engrossed in the digital interaction and distracted from real world condition. This skepticism stems from the understanding that, in high-pressure scenarios, the operation of these systems could potentially extend the user’s interaction time with the app. The implications of our user research suggest a significant need to minimize technological disruptions for users of an earthquake navigation app. This is crucial as any delay, such as waiting for AR to initialize or adjusting the volume to hear voice assistant instructions, can escalate psychological stress for users, especially in life-threatening situations during an earthquake.

Iterated Prototype

The first component, User Experience Design, involves insights related to the design of the navigation user interface. It emphasizes the imperative nature of ensuring the rapid usability of the earthquake navigation app, a crucial element given the heightened tension and time sensitivity users experience during an earthquake. The prompt usability of the app is pivotal to guarantee that the app’s response and feedback are immediate and efficient, necessitating a design free of complicated operations. Additionally, our expert user research reveals a cautious view regarding the integration of augmented reality and voice assistant technologies during earthquakes, due to the limited field of view and over-immersion, making users becomes engrossed in the digital interaction and distracted from real world condition. This skepticism stems from the understanding that, in high-pressure scenarios, the operation of these systems could potentially extend the user’s interaction time with the app. The implications of our user research suggest a significant need to minimize technological disruptions for users of an earthquake navigation app. This is crucial as any delay, such as waiting for AR to initialize or adjusting the volume to hear voice assistant instructions, can escalate psychological stress for users, especially in life-threatening situations during an earthquake.

In the iteration, quake survivors suggested reducing the

cognitive load to use our app in a stressful crisis condition.

The interviews have helped us to empathize with users' minds as

we repeated the design thinking process to iterate our

prototype. Based on our users' evaluation, we kept two main

features 1) call emergency, and 2) shelter or hospital

navigation. Our iterated prototype is shown in Fig 2. If users

are trapped in the building, the app will provide a button to

call for rescue and should automatically share users' locations.

Our application should also provide information on users'

current addresses, in case the GPS location needs to be verbally

reported to the rescue facility. If users just escaped from the

building, and want to look for a nearby safe place, the app will

provide navigation to both hospitals and shelters nearby with

only one safest route with a relatively short path.

Fig 4 & 5. Iterated Prototype

The second component, Algorithm Modification, discusses

alterations made to the algorithm. We posit that the

superiority of the A-Star algorithm over other routing

algorithms is its capability to execute swiftly, its minimal

reliance on extensive CPU power, and its ability to function

locally in scenarios where the internet is unavailable, a

common occurrence during earthquakes due to network

disruptions. Furthermore, we have enhanced the algorithm by

incorporating considerations of city layers and

infrastructure. We have also integrated concepts from the

ant colony algorithm, acknowledging the human inclination to

seek safe zones, thereby imbuing the A-Star algorithm with

this capability. The enhancements to the A-Star algorithm

are segmented into four steps: 1) creating a dataset based

on roads; 2) establishing an empty dataset for weight; 3)

enabling the updating of weight contingent on

infrastructure; and 4) permitting the modification of weight

based on safety, correlated to human behavior. Subsequent

sections will delve into the detailed process of these

specific algorithmic improvements.

Modification on A-Star algorithm

The shortest route has been intensively investigated in

computer science in path-finding issues owing to its broad

applications such as network routing protocols, traffic

management, and transportation systems

\cite{stern2019multi}. A-Star search method, Dijkstra, and

Ant Colony Optimization are been studied among all other

algorithms documented in the literature that address the

shortest route between two geographical places. While

Dijkstra obtains the best answer by investigating all

potential pathways, A-Star search utilizes a heuristic

function to determine the shortest path. A-Star is a BFS

algorithm that uses a heuristic function to find the

shortest path from a source node to a destination node in

a grid.

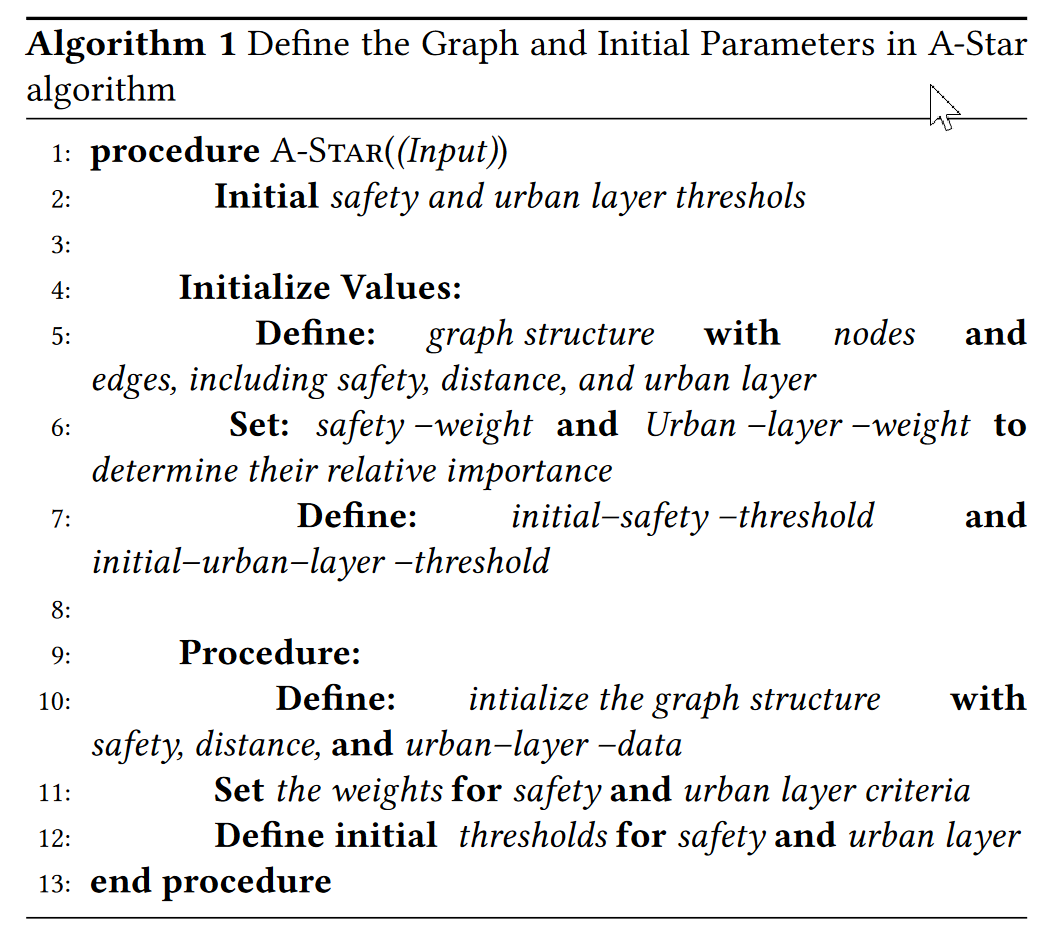

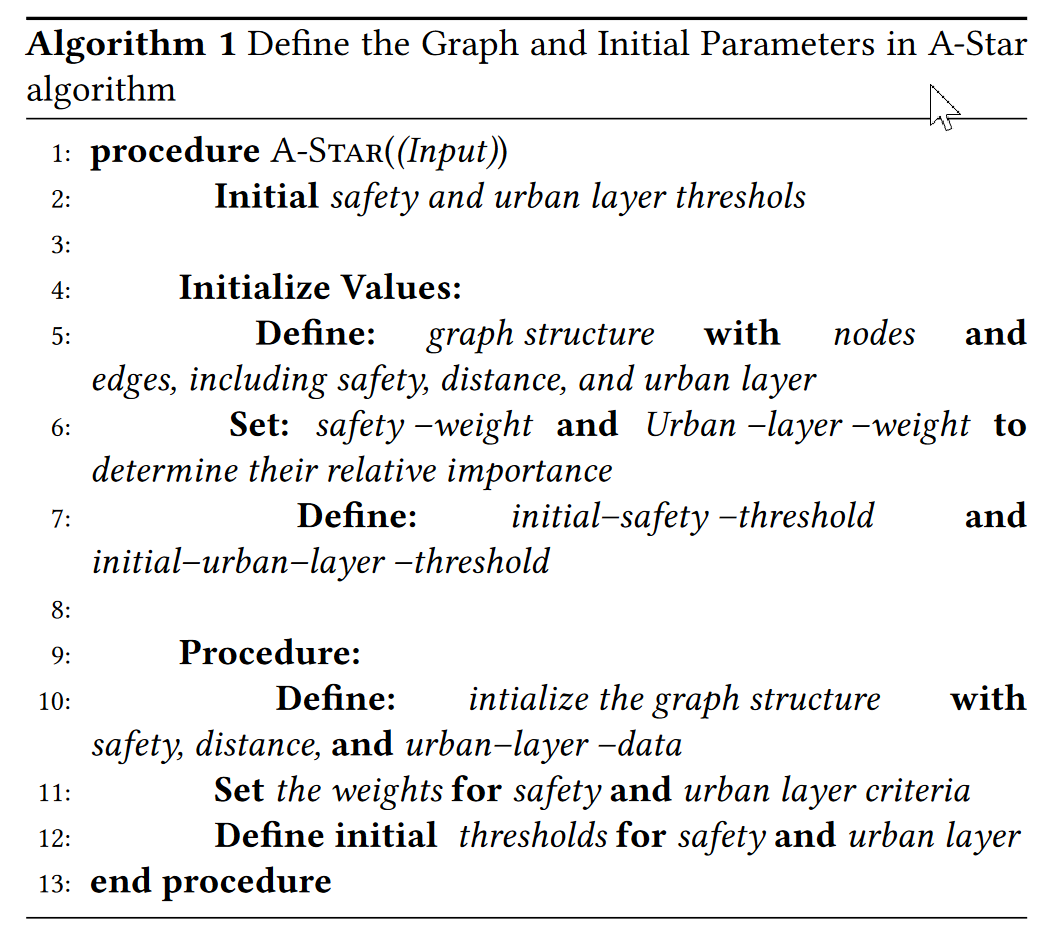

This research presents an efficient algorithm based on A-Star search to find the safest route dynamically between two locations. Safety and infrastructure data are integrated into a graph representation of the environment. Adaptive thresholds are used to filter out hazardous routes. A-star search guided by a cost function combining safety and appearance scores can rapidly find optimal routes. The algorithm is extended to work in real time by continuously updating the graph with simulated live data and re-running route searches to deal with dynamic changes. The algorithm is implemented in four steps:

In the first step, we initialize the data structure of the graph that shows the city centers and the connections (the edges) between them. Each edge in the chart contains information about safety, distance, and urban layers. Safety_Weight and urban\textendash layer_Weight are defined to assign different weights to safety and infrastructure criteria. These weights determine the relative importance of each criterion in the optimization process. These thresholds determine whether a road is considered safe or has enough infrastructure to choose the route as a safe path (Algorithm 1).

Here, we set up a route\textendash cache dictionary. This cache is used to store calculated routes and their associated safety and infrastructure thresholds. It helps to avoid extra calculations by checking if a path has already been calculated (Algorithm 2).

This is the core of the code, the A-Star algorithm. It is responsible for finding the safest route by taking into account the safety and appearance criteria. The algorithm checks whether the route from start to target is calculated with the safety and apparent thresholds given before using the route\textendash cache. If the cache is cached, it retrieves the path from the cache to avoid recomputing. The algorithm maintains a priority queue (open\textendash set) to explore the path efficiently. It calculates a dynamic safety threshold (dynamic\textendash safety\textendash threshold) and appearance threshold (dynamic\textendash urbanlayer\textendash threshold) based on current conditions. The safety and infrastructure threshold are used to determine whether a road is suitable for being on track. The algorithm selects a path with the highest safety and infrastructure stability while minimizing the overall cost (taking into account both safety weight and infrastructure weight). Once the safest route is found, it is stored in the route\textendash cache to avoid additional calculations. This step consists primarily of the A-Star customized algorithm according to the demands of the research which includes several mathematical components.

First of all, the heuristic function estimates the cost

from the current node to the target node using Euclidean

distance or a similar metric. Second, dynamic thresholds

are calculated based on current conditions. These

thresholds can be defined based on specific criteria or

conditions, depending on the scope of the problem. Third,

cost calculations or Probation cost (tentative\textendash

g\textendash cost) for each neighboring node is calculated

based on the cost of the current node, the distance to the

neighbor and the domain-specific factors. The combined

cost (f\textendash cost) is calculated as the weighted sum

of safety and infrastructure scores.

First of all, the heuristic function estimates the cost

from the current node to the target node using Euclidean

distance or a similar metric. Second, dynamic thresholds

are calculated based on current conditions. These

thresholds can be defined based on specific criteria or

conditions, depending on the scope of the problem. Third,

cost calculations or Probation cost (tentative\textendash

g\textendash cost) for each neighboring node is calculated

based on the cost of the current node, the distance to the

neighbor and the domain-specific factors. The combined

cost (f\textendash cost) is calculated as the weighted sum

of safety and infrastructure scores.

Safety_weight are user_defined weights that reflect the relative importance of safety and infrastructure metrics. These weights can be adjusted based on the needs of the problem. Safety and infrastructure represent safety scores and the infrastructure associated with the edge being considered (Algorithm 3).

This step defines the function calculate route\textendash features which calculates the level of safety, total distance, and overall infrastructure of a given path. Through each edge (road) in the path it repeats, retrieves the safety data, distance, and infrastructure from the graph, and sums up values. The function returns a dictionary containing these trajectory properties. In this step, the safety level of a route is calculated as the product of the safety score along the path. For each edge on the path, the safety score is multiplied.

\text{Safety level} = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \text{Safety score}_{i}

Safety Score i indicates the safety score associated with edge i on the route. n is the total number of route edges. Also, the total distance of the route is the sum of distances of all edges in the path which is calculated by the formula below. In this formula, n is the total number of route edges, and distance i indicates the distance associated with edge i on the route.

Safety Level = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \text{Safety Score}_{i}

The infrastructure score(urban layer) is the sum of apparent points for all edges of the path. The i infrastructure represents the apparent score associated with edge i in the route. And n The total number of edges in the route.

\text{Total Appearance} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \text{infrastructure}_{i}

Finally, these steps together enable the code to continuously update safety and infrastructure data, apply the A-Star algorithm with customizations, and calculate and display track properties in real time. This code ensures efficient route optimization while considering dynamic thresholds and minimizing redundant computations (Algorithm 4).

This research presents an efficient algorithm based on A-Star search to find the safest route dynamically between two locations. Safety and infrastructure data are integrated into a graph representation of the environment. Adaptive thresholds are used to filter out hazardous routes. A-star search guided by a cost function combining safety and appearance scores can rapidly find optimal routes. The algorithm is extended to work in real time by continuously updating the graph with simulated live data and re-running route searches to deal with dynamic changes. The algorithm is implemented in four steps:

In the first step, we initialize the data structure of the graph that shows the city centers and the connections (the edges) between them. Each edge in the chart contains information about safety, distance, and urban layers. Safety_Weight and urban\textendash layer_Weight are defined to assign different weights to safety and infrastructure criteria. These weights determine the relative importance of each criterion in the optimization process. These thresholds determine whether a road is considered safe or has enough infrastructure to choose the route as a safe path (Algorithm 1).

Here, we set up a route\textendash cache dictionary. This cache is used to store calculated routes and their associated safety and infrastructure thresholds. It helps to avoid extra calculations by checking if a path has already been calculated (Algorithm 2).

This is the core of the code, the A-Star algorithm. It is responsible for finding the safest route by taking into account the safety and appearance criteria. The algorithm checks whether the route from start to target is calculated with the safety and apparent thresholds given before using the route\textendash cache. If the cache is cached, it retrieves the path from the cache to avoid recomputing. The algorithm maintains a priority queue (open\textendash set) to explore the path efficiently. It calculates a dynamic safety threshold (dynamic\textendash safety\textendash threshold) and appearance threshold (dynamic\textendash urbanlayer\textendash threshold) based on current conditions. The safety and infrastructure threshold are used to determine whether a road is suitable for being on track. The algorithm selects a path with the highest safety and infrastructure stability while minimizing the overall cost (taking into account both safety weight and infrastructure weight). Once the safest route is found, it is stored in the route\textendash cache to avoid additional calculations. This step consists primarily of the A-Star customized algorithm according to the demands of the research which includes several mathematical components.

Safety_weight are user_defined weights that reflect the relative importance of safety and infrastructure metrics. These weights can be adjusted based on the needs of the problem. Safety and infrastructure represent safety scores and the infrastructure associated with the edge being considered (Algorithm 3).

This step defines the function calculate route\textendash features which calculates the level of safety, total distance, and overall infrastructure of a given path. Through each edge (road) in the path it repeats, retrieves the safety data, distance, and infrastructure from the graph, and sums up values. The function returns a dictionary containing these trajectory properties. In this step, the safety level of a route is calculated as the product of the safety score along the path. For each edge on the path, the safety score is multiplied.

\text{Safety level} = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \text{Safety score}_{i}

Safety Score i indicates the safety score associated with edge i on the route. n is the total number of route edges. Also, the total distance of the route is the sum of distances of all edges in the path which is calculated by the formula below. In this formula, n is the total number of route edges, and distance i indicates the distance associated with edge i on the route.

Safety Level = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \text{Safety Score}_{i}

The infrastructure score(urban layer) is the sum of apparent points for all edges of the path. The i infrastructure represents the apparent score associated with edge i in the route. And n The total number of edges in the route.

\text{Total Appearance} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \text{infrastructure}_{i}

Finally, these steps together enable the code to continuously update safety and infrastructure data, apply the A-Star algorithm with customizations, and calculate and display track properties in real time. This code ensures efficient route optimization while considering dynamic thresholds and minimizing redundant computations (Algorithm 4).

Video Presentation

Video presentation