Published on 28th Mar 2024 –

Updated on 11th Jun 2024

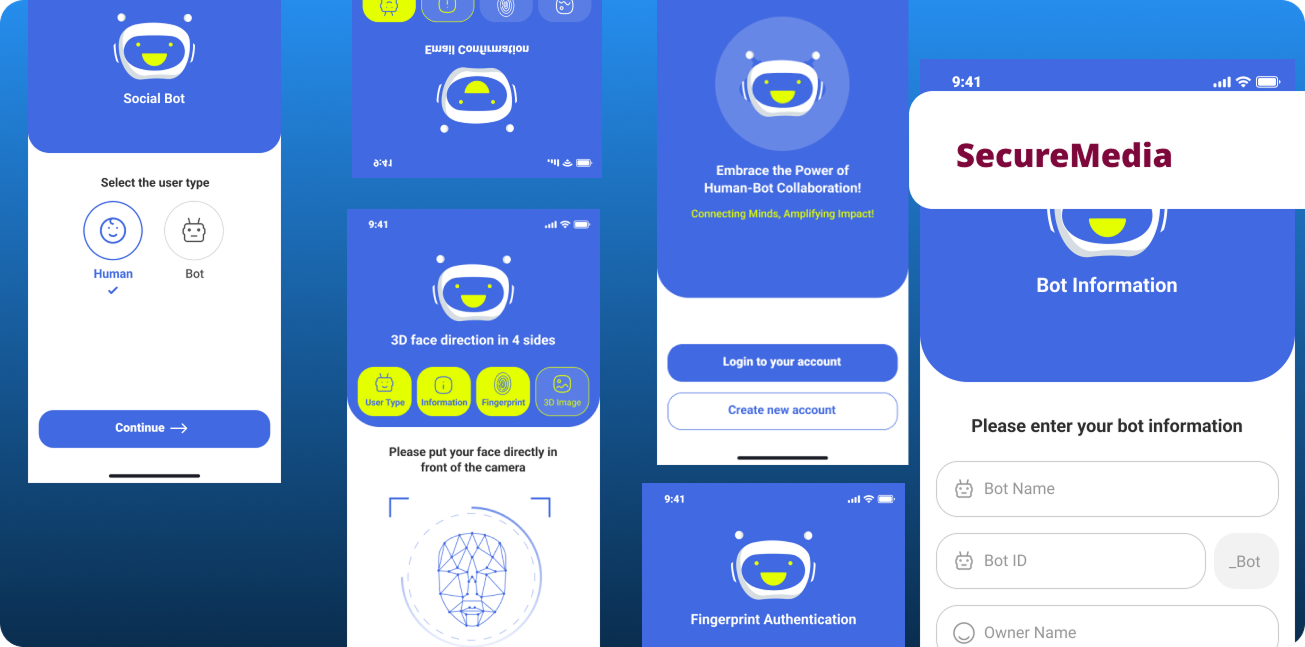

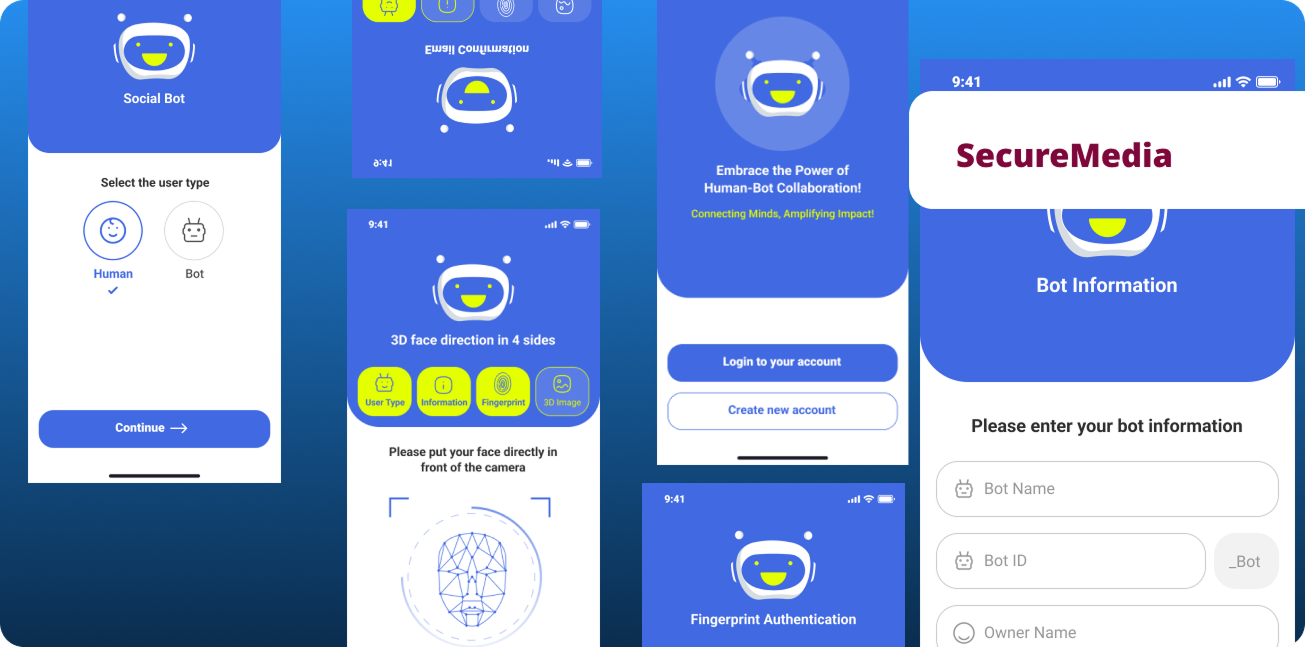

Bots and Chatbots vs. Humans: Your identity will be safe in

SecureMedia App

Fig 0. SecureMedia Cover Presentation

Bots and Chatbots are ubiquitous in everyday life.

Surprisingly, although they play a major role in Internet

fraud, they have received limited attention in HCI. The

primary concern is whether our identity is vulnerable to being

exploited by bots for identity fraud or other fraudulent

activities, and how we can mitigate this risk. We provide the

groundwork for understanding bots' capabilities and possible

weaknesses through an empirical study of the 16 participants

via a narrative study. Furthermore, we examine the components

of human identity and emphasize their significance in both

personal and societal contexts. We also explore the ethical

implications of data privacy and security, as well as the

potential ramifications of compromised human identity. In

discussing our findings, we suggest future research

initiatives to address these dangers. We offer frameworks and

remedies for bots abusing human identity in three phases:

before fraud, during fraud, and after fraud.

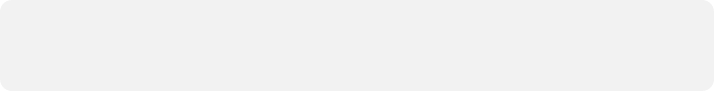

Research Questions

Methodology

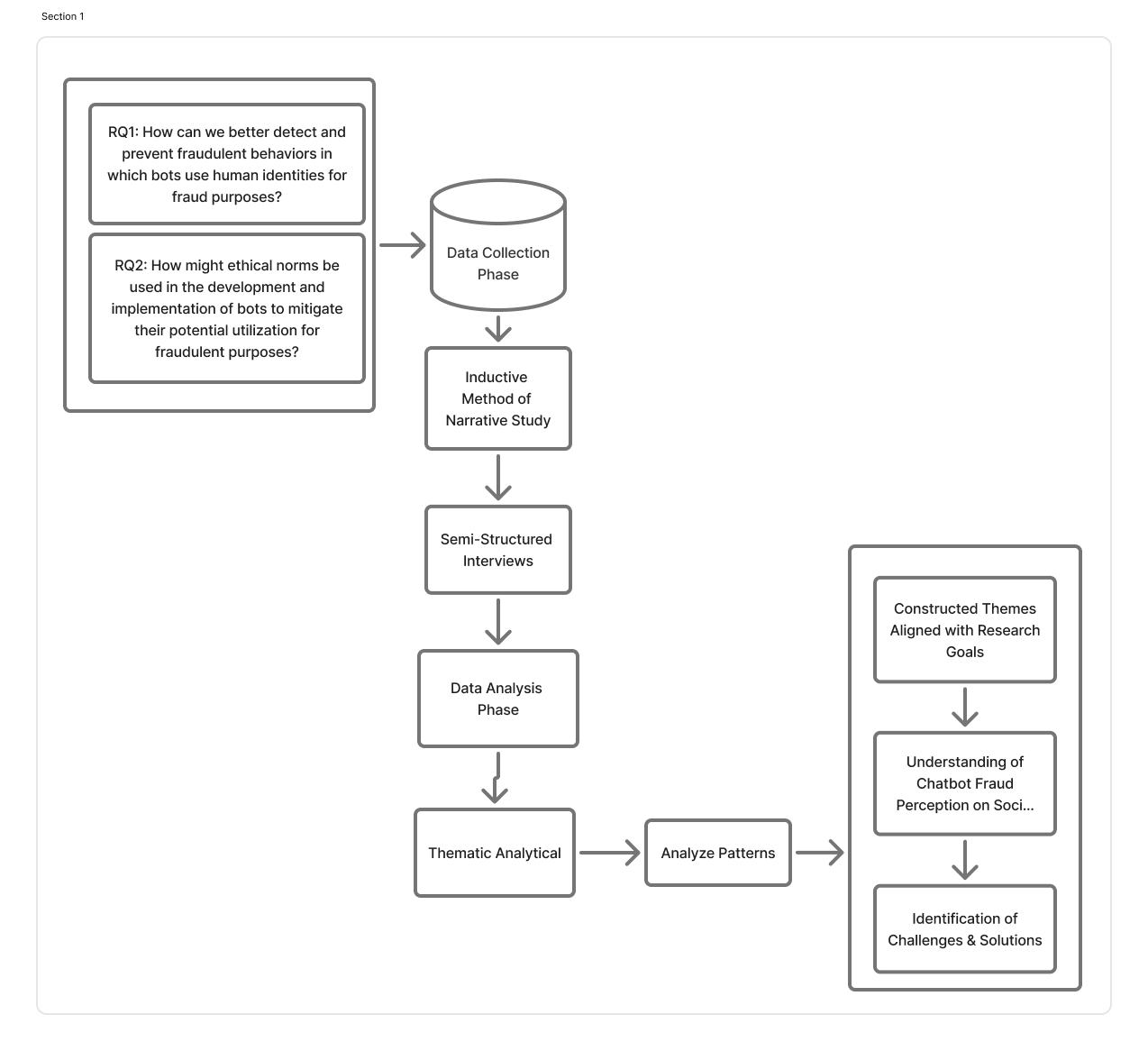

In general, since social media and chatbots have been linked to

a variety of human life aspects, including social support and

health outcomes, it is somewhat surprising that there is so

little research examining how they use links to fraud and

scamming and ways to make them easily identifiable on social

media platforms. In response to the research question, we used a

qualitative approach to understand how people perceive chatbots

as fraudsters on different social media platforms. The collected

qualitative data were analyzed using a thematic analytical

framework to construct themes that aligned with the study’s

goals and questions. Thematic analysis is widely used in

qualitative research and can be applied to a variety of

epistemologies and research questions. In statistics, it is used

to identify, analyze, organize, describe, and report themes

found in data. Narrative analysis as qualitative research is

used for interpreting and presenting stories from interviews. To

collect data inductive method of narrative study is used and

then to identify the challenges, semi-structured interviews were

conducted, in which open-ended questions were posed to allow

interviewers to explore topics that emerged during the

interview.

Fig 3. Research process overview and analysis workflow

Participants

The study included a sample of 16 users who were interviewed. A

significant proportion of the interviewees were men (11/16 and

68.7 Percent) and (11/16) were from Iran. The age range of the

participants spanned from 27 to 35 years, with a mean age of 30

years. Most of the participants used telegram during fraud and

were victims (10/16 and 62.5 Percent). For further details

regarding participant demographics, please refer to Tab1. To

ensure ethical standards, participants were explicitly informed

that their personal information would not be collected and would

not receive any form of compensation for their participation.

Narrative Study

Through this narrative research, we provided a rich and

holistic view of identity fraud in social media platforms by

understanding and interpreting the experiences of victims

scammed by bots and chatbots. A total of sixteen participants

were interviewed, who experienced a scam on social media or

developed a bot for targeting people as hackers. Due to the

participants' circumstances, some interviews (P4, P9, and P14)

were conducted in person. The remaining 13 interviews were

conducted via video or voice call. We started the interviews

with a short explanation of the research objectives and

guidelines, followed by demographic questions. After that, the

interview script addressed three main topics: (i) a discussion

about fraud; (ii) the main challenges including challenges

before, during, and after crime; and (iii) the solutions to

those challenges. An average of 40 minutes was spent on each

interview conducted by the authors of this paper, both

remotely and in person. We qualitatively analyzed the

interview transcripts, performing open and axial coding

procedures throughout multiple rounds of the inductive method

of narrative analysis. We started by applying open coding,

whereby we identified the main points related to the feelings

and challenges brought by the interaction, adoption, and

trusting chatbots, and finally collected the pieces of advice

by victims and affected for recognizing bots and avoiding

being victims.

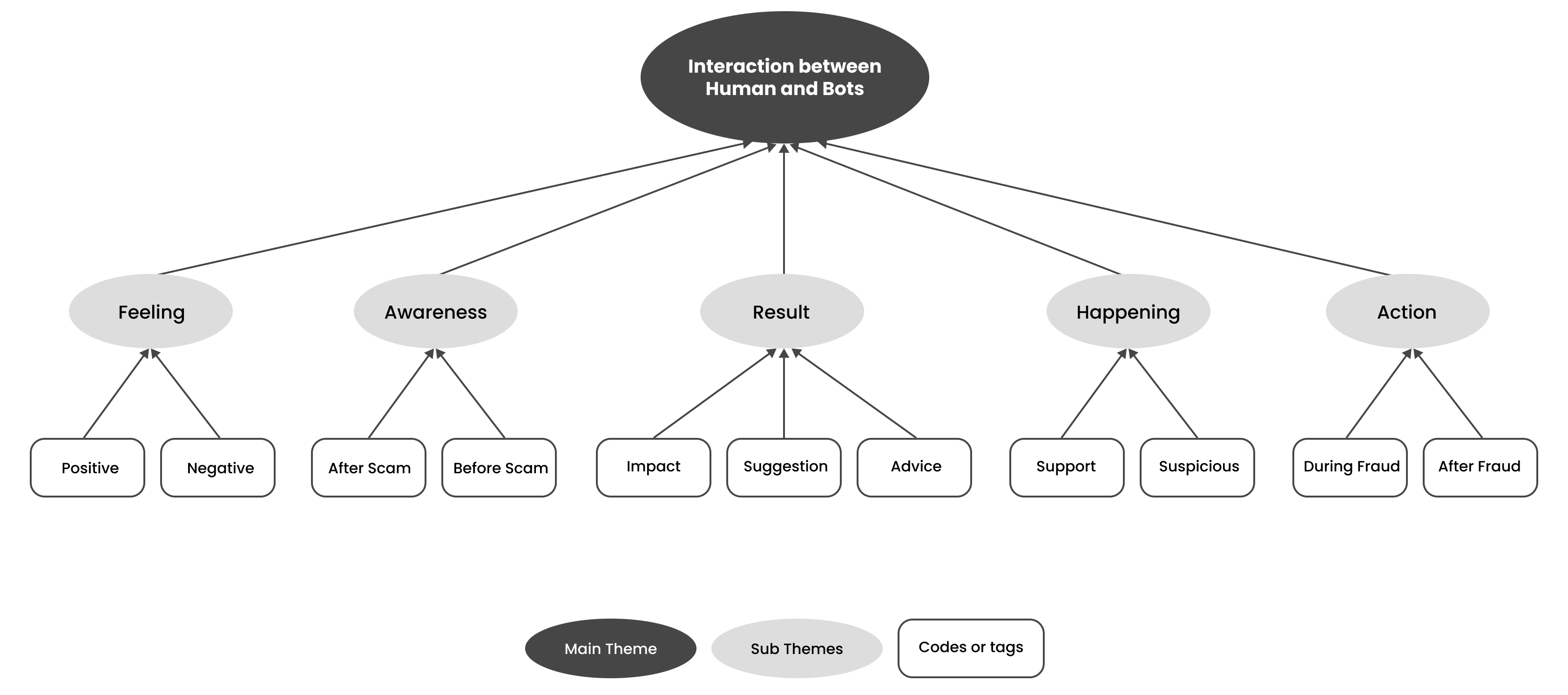

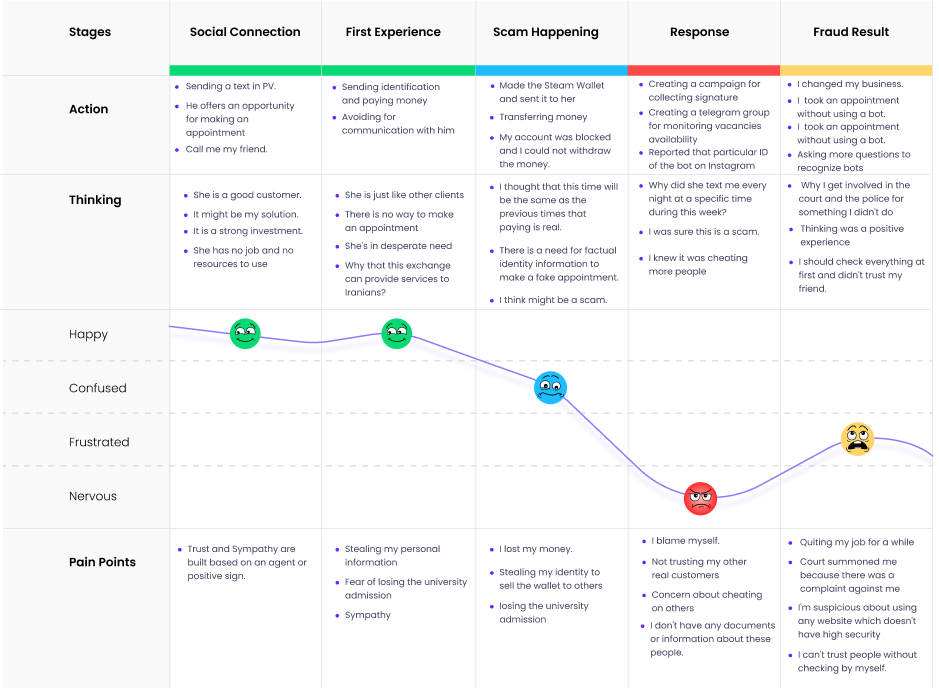

Following the coding interviews, we developed a systematic

coding framework, as shown in Fig1. A key component of this

framework was the victims' emotional experiences, including both

positive and negative effective states. Through the integration

of this emotional dimension into the coding system, a nuanced,

multidimensional analysis of the phenomenon can be conducted.

Such a comprehensive understanding is instrumental in the

development of more efficacious preventative and remedial

strategies. Within our thematic framework, the level of

awareness of the victim prior to and following the fraudulent

event emerged as a crucial aspect. Knowledge and situational

awareness are crucial to enabling victims to distinguish between

human and chatbot perpetrators in this theme. To develop

targeted intervention strategies, we plan to investigate the

impact of cognitive and awareness-related factors on the

victim's ability to accurately identify the fraudster. The

themes of 'Happening' and 'Action' were identified as two

critical dimensions within our coding framework, each focusing

on the cognitive and behavioral responses of victims during and

subsequent to the fraudulent event. In the result section, the

theme looks at how such fraudulent activities impact the

lifestyles and behaviors of victims. A systematic code was also

applied to victims' post-experience recommendations and

suggested remedial measures.

Fig 2. Systematic coding framework for analyzing chatbot fraud experiences

Examining real-world examples of bots

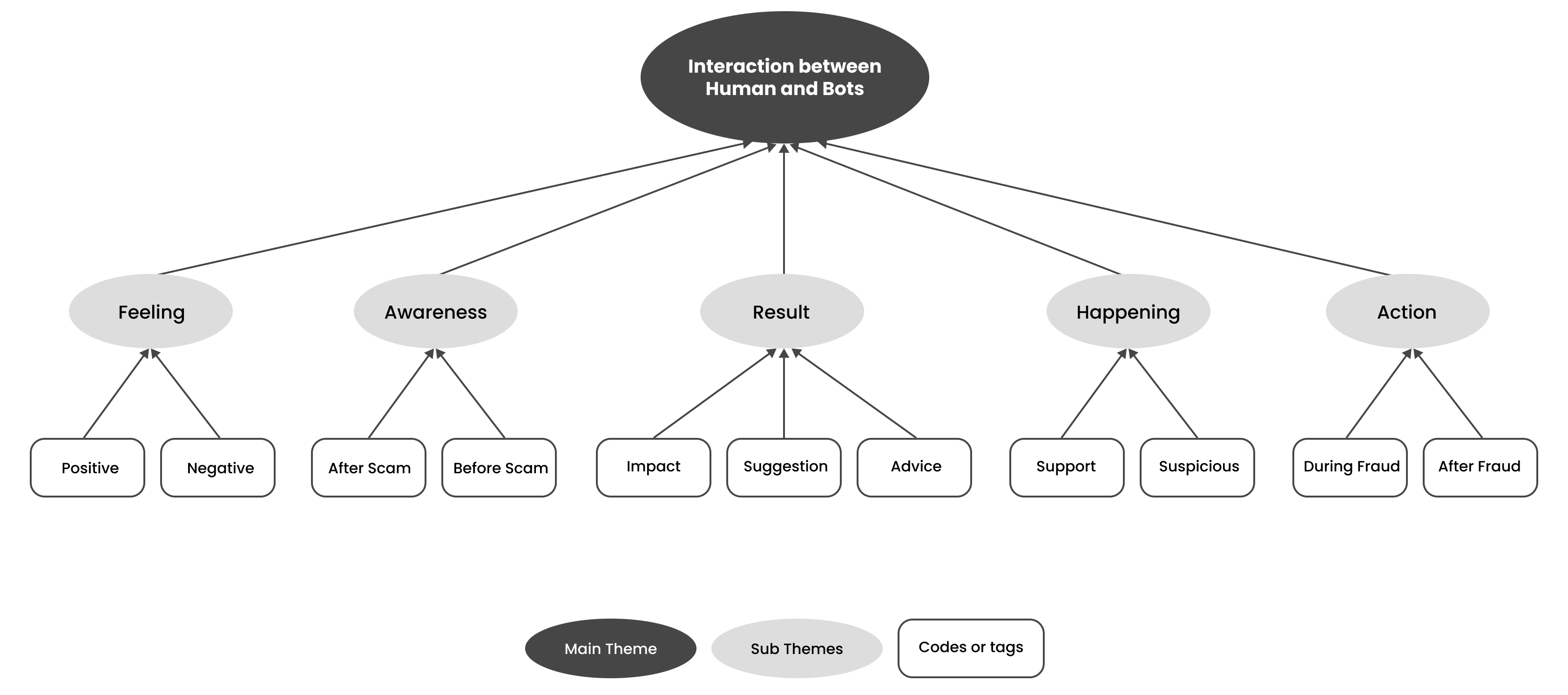

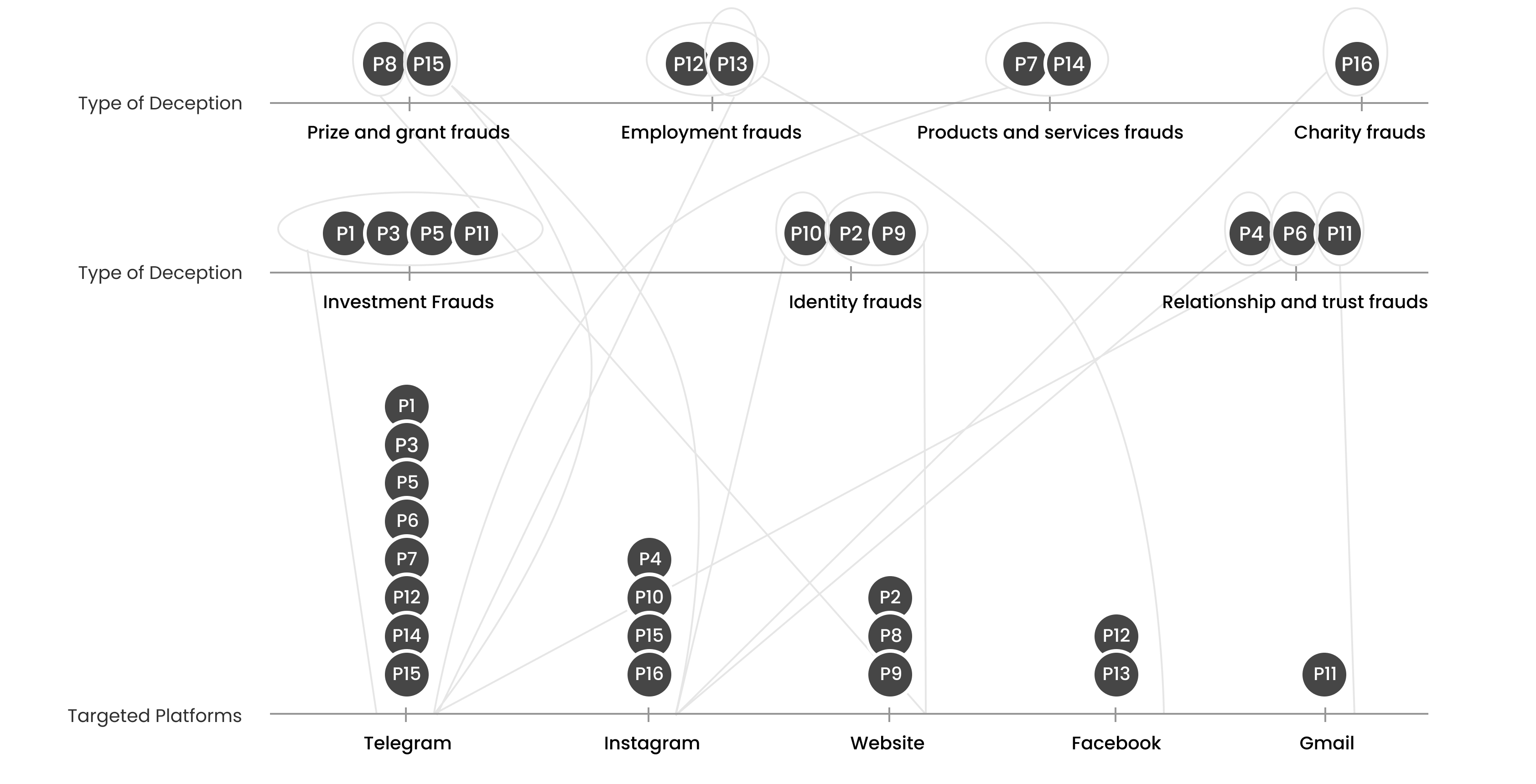

In the current investigation, interviews were conducted with

individuals who had fallen prey to fraudulent schemes.

Initially, participants were under the impression that human

actors were behind the deception. According to the interview

transcripts and the interviewees' viewpoints, it is more

likely that the malicious entities were automated chatbots or

bots, rather than human beings. An array of online platforms

was used for these deceptive activities, including social

media and websites. A total of 16 participants participated,

although the recruitment process faced challenges due to

potential participants' hesitancy, often stemming from

embarrassment or privacy concerns. Historically, fraudulent

activities have been predominantly carried out via email.

However, with the proliferation of social media platforms, a

notable shift has been observed in the modus operandi of these

fraudulent acts. Current evidence suggests a preference for

using social media platforms as the medium for executing

scams. The participant recruitment was streamlined via a

diversified platform outreach strategy, encompassing Telegram,

Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn. Participants

received information on Ensuring Ethical and Legal Compliance

concerning stringent data privacy measures.

Fig 3. Social media used by each participant and categories of fraud

Finding

Our exploration into various themes related to chatbot scams has

revealed insightful findings that contribute to our

understanding of this pervasive problem. This investigation has

focused on the following themes, including awareness before and

during scams, the impact on individuals and society, prevention

strategies, actions during and after encountering scams,

recognizing suspicious activities, and the emotional experiences

of scam victims. Through analyzing real-life case studies, we

have gained valuable insights into these themes, shedding light

on the complexities surrounding scams and providing design

recommendations to mitigate their harmful effects. At the end,

we designed SecureMedia based on our study.

Threats to Human Identity

Based on participant interviews, several significant threats

to human identity emerged in interactions with chatbots and

other automated systems. Participants described multiple

instances in which malicious actors accessed, compromised, and

misused personal information. These findings underscore the

importance of understanding identity-related threats in order

to better protect individuals.

P1’s narrative vividly illustrates the high-stakes reality of identity harm enabled by bots and chatbots. In our interview, P1 recounted a troubling incident in which his identity was exploited to facilitate fraudulent activity. In this case, the perpetrator impersonated P1 using a bot and carried out financial transactions that resulted in fraud and subsequent legal consequences:

“This offender used a bot to deceive people and steal money from them using my identity; I am convinced that behind every bot, there is a person in charge.” (P1)

P1 also emphasized the intense psychological distress caused by the misuse of personal information, noting that identity theft can contribute to extreme outcomes, including suicidal ideation. This highlights the severe personal impact of identity theft in contexts involving chatbots and automated systems, particularly in relation to privacy and security.

In addition, P9 described how bots and chatbots can psychologically manipulate users to build trust and deceive them. Because these systems can be designed to mimic human behavior and strategically exploit social and cognitive cues, they may appear even more convincing than human scammers. As P9 explained, identity theft techniques have become increasingly sophisticated:

“They were initially programmed in a way that tried to mimic human behavior or human cognition. They get people to like them and trust them by using psychological factors; I think they are even better than real humans who try to scam you.” (P9)

Meanwhile, P10 stressed the violation of personal identity and its exploitation for financial gain: “It is like intimidating my personal identity and using it for money.” (P10) This reflects the deeply personal nature of identity theft and how victims often experience it as an intrusive, dehumanizing form of harm.

P15 expanded on the broader, commercial dimensions of these threats by describing how stolen data can be treated as a commodity. They recounted an instance in which a company purchased user data collected through bots, after which the data was analyzed, refined, and used for targeted marketing initiatives. This example demonstrates how data breaches can be monetized and leveraged for profit:

“They often sell this information. For example, I know a company that bought the information collected from users by bots. Even this information was completely analyzed and refined.” (P15)

Finally, many participants expressed a shared misconception that they were unlikely to become victims of scams. P5 and P16 acknowledged that they believed such incidents would never happen to them, despite being knowledgeable about technology and bots. Similarly, P7 suggested that fraud is often successful because people are not sufficiently alert and assume they will not be targeted. This view was echoed by P4, who reported strong familiarity with bots while still underestimating their own vulnerability. Even participants who considered themselves well-informed, such as P1, admitted that overconfidence contributed to negative outcomes. Collectively, these accounts highlight the risks of underestimating identity-based threats and show how victimization can stem from the false belief that “it won’t happen to me.”

P1’s narrative vividly illustrates the high-stakes reality of identity harm enabled by bots and chatbots. In our interview, P1 recounted a troubling incident in which his identity was exploited to facilitate fraudulent activity. In this case, the perpetrator impersonated P1 using a bot and carried out financial transactions that resulted in fraud and subsequent legal consequences:

“This offender used a bot to deceive people and steal money from them using my identity; I am convinced that behind every bot, there is a person in charge.” (P1)

P1 also emphasized the intense psychological distress caused by the misuse of personal information, noting that identity theft can contribute to extreme outcomes, including suicidal ideation. This highlights the severe personal impact of identity theft in contexts involving chatbots and automated systems, particularly in relation to privacy and security.

In addition, P9 described how bots and chatbots can psychologically manipulate users to build trust and deceive them. Because these systems can be designed to mimic human behavior and strategically exploit social and cognitive cues, they may appear even more convincing than human scammers. As P9 explained, identity theft techniques have become increasingly sophisticated:

“They were initially programmed in a way that tried to mimic human behavior or human cognition. They get people to like them and trust them by using psychological factors; I think they are even better than real humans who try to scam you.” (P9)

Meanwhile, P10 stressed the violation of personal identity and its exploitation for financial gain: “It is like intimidating my personal identity and using it for money.” (P10) This reflects the deeply personal nature of identity theft and how victims often experience it as an intrusive, dehumanizing form of harm.

P15 expanded on the broader, commercial dimensions of these threats by describing how stolen data can be treated as a commodity. They recounted an instance in which a company purchased user data collected through bots, after which the data was analyzed, refined, and used for targeted marketing initiatives. This example demonstrates how data breaches can be monetized and leveraged for profit:

“They often sell this information. For example, I know a company that bought the information collected from users by bots. Even this information was completely analyzed and refined.” (P15)

Finally, many participants expressed a shared misconception that they were unlikely to become victims of scams. P5 and P16 acknowledged that they believed such incidents would never happen to them, despite being knowledgeable about technology and bots. Similarly, P7 suggested that fraud is often successful because people are not sufficiently alert and assume they will not be targeted. This view was echoed by P4, who reported strong familiarity with bots while still underestimating their own vulnerability. Even participants who considered themselves well-informed, such as P1, admitted that overconfidence contributed to negative outcomes. Collectively, these accounts highlight the risks of underestimating identity-based threats and show how victimization can stem from the false belief that “it won’t happen to me.”

Strategies of Deception: Chatbots' Manipulative Tactics in

Action

The realm of OSN fraud shows how chatbots use strategic

deception to convince unsuspecting users that they are

interacting with real people. Interviewees P1 and P10 both

described experiences in which their online identities were

hijacked and manipulated by chatbots. These systems imitate

usernames and profiles to create an illusion of authenticity,

fostering familiarity and trust among potential victims. This

strategy aligns with P15’s observations, which suggest that

chatbots deliberately select usernames resembling reputable

entities to evoke credibility. As P15 explained:

“This bot chose its name similar to famous and reputable exchanges in the world, which made users who search for its name think that it is the same reputable exchange, and many times unconsciously, the user trusts this bot after seeing this famous name.” (P15)

Furthermore, as noted by P12, P13, and P14, chatbots exploit job-seeking behaviors, demonstrating their effectiveness in capitalizing on users’ vulnerabilities. Fraudsters target individuals seeking employment by monitoring social media posts and tracking job-related discussions, reflecting an acute understanding of users’ goals and motivations. P12 reported being deceived by a sophisticated scammer who exploited her circumstances after she pursued illegal employment. Meanwhile, P13 and P14 described being lured by individuals who promised jobs in exchange for money, only to take the payment and then block them.

The experiences of P3, P5, and P16 reveal additional manipulative communication tactics. P3 described the deliberate use of Google Translate–generated replies to avoid answering questions directly—an approach echoed by P5, who noted that chatbots often rely on vague and ambiguous messages that obscure their non-human nature. Similarly, P16 and P11 encountered a chatbot that initiated contact and then transitioned seamlessly into more human-like interactions, drawing users deeper into deception. Their accounts also highlight the exploitation of emotional triggers: chatbots fabricated detailed narratives involving personal tragedy and wealth, appealing to empathy and compassion to strengthen emotional attachment and trust. For example, P16 stated:

“The messages were that this lady had lost her husband. She said that she is suffering from cancer and will probably die in the next few months and has a lot of wealth and wants to dedicate this wealth to the needy.” (P16)

In addition, P3, P5, and P15 described chatbots generating “profitable” trading signals, leveraging users’ desire for quick financial gain. P7—an experienced hacker interviewed via Telegram voice messages to protect anonymity—provided insight into how these tactics are deliberately designed and deployed. Notably, P7’s descriptions of deceptive methods aligned closely with the strategies used against P3 and P5, illustrating systematic patterns in hacker behavior and in how victims interpret these interactions. Overall, as reflected in the accounts of P5 and P16, chatbots manipulate human psychology through a combination of financial incentives and emotional connection. This underscores the multidimensional nature of chatbot-driven fraud, where scripted narratives blending personal tragedy, promised profits, and companionship are used to shape users’ emotions and cultivate sustained trust.

“This bot chose its name similar to famous and reputable exchanges in the world, which made users who search for its name think that it is the same reputable exchange, and many times unconsciously, the user trusts this bot after seeing this famous name.” (P15)

Furthermore, as noted by P12, P13, and P14, chatbots exploit job-seeking behaviors, demonstrating their effectiveness in capitalizing on users’ vulnerabilities. Fraudsters target individuals seeking employment by monitoring social media posts and tracking job-related discussions, reflecting an acute understanding of users’ goals and motivations. P12 reported being deceived by a sophisticated scammer who exploited her circumstances after she pursued illegal employment. Meanwhile, P13 and P14 described being lured by individuals who promised jobs in exchange for money, only to take the payment and then block them.

The experiences of P3, P5, and P16 reveal additional manipulative communication tactics. P3 described the deliberate use of Google Translate–generated replies to avoid answering questions directly—an approach echoed by P5, who noted that chatbots often rely on vague and ambiguous messages that obscure their non-human nature. Similarly, P16 and P11 encountered a chatbot that initiated contact and then transitioned seamlessly into more human-like interactions, drawing users deeper into deception. Their accounts also highlight the exploitation of emotional triggers: chatbots fabricated detailed narratives involving personal tragedy and wealth, appealing to empathy and compassion to strengthen emotional attachment and trust. For example, P16 stated:

“The messages were that this lady had lost her husband. She said that she is suffering from cancer and will probably die in the next few months and has a lot of wealth and wants to dedicate this wealth to the needy.” (P16)

In addition, P3, P5, and P15 described chatbots generating “profitable” trading signals, leveraging users’ desire for quick financial gain. P7—an experienced hacker interviewed via Telegram voice messages to protect anonymity—provided insight into how these tactics are deliberately designed and deployed. Notably, P7’s descriptions of deceptive methods aligned closely with the strategies used against P3 and P5, illustrating systematic patterns in hacker behavior and in how victims interpret these interactions. Overall, as reflected in the accounts of P5 and P16, chatbots manipulate human psychology through a combination of financial incentives and emotional connection. This underscores the multidimensional nature of chatbot-driven fraud, where scripted narratives blending personal tragedy, promised profits, and companionship are used to shape users’ emotions and cultivate sustained trust.

Unveiling the Mask: Identifying Distinctive Behaviors of

Deceptive Chatbots

Chatbot habits frequently trigger red flags, prompting users

to mistrust the legitimacy of their conversations. By

combining the experiences of the interviewees, a discernable

pattern emerges, revealing warning indicators that elicit

doubt and skepticism. Interviewees P6 and P11 found a pattern

of limited and repetitive communication strategies used by

chatbots. P6 noticed suspicions due to single-sentence

responses and monotonous repetition, while P11 noted a lack of

human emotion in messages.“ Another thing that made me dubious

was that she used to write single sentences an didn’t

completely converse. ” P13 also observed brief and formal

responses, a common behavior in chatbot encounters:

“ Throughout our chat, she continued responding briefly, like a computer or a robot. ” Interestingly, P1 adds a temporal component to these behaviors, emphasizing the chatbot’s consistent message at specified times—a behavior that is discordant in true human encounters.“ It’s amazing how she would send me a message at the same time every night. ” P9 and P10 emphasize the clear distinction between human and machine responses. P9 elucidates chatbots’ original programming to mimic human intellect and behavior, and as P10 emphasizes, this purpose is visible in the starkly mechanical aspect of their communication. Similarly, when enquiries are made in multiple languages, P4 reveals discordant responses in chatbot conversations, casting doubt on the nature of the interaction.

“ Throughout our chat, she continued responding briefly, like a computer or a robot. ” Interestingly, P1 adds a temporal component to these behaviors, emphasizing the chatbot’s consistent message at specified times—a behavior that is discordant in true human encounters.“ It’s amazing how she would send me a message at the same time every night. ” P9 and P10 emphasize the clear distinction between human and machine responses. P9 elucidates chatbots’ original programming to mimic human intellect and behavior, and as P10 emphasizes, this purpose is visible in the starkly mechanical aspect of their communication. Similarly, when enquiries are made in multiple languages, P4 reveals discordant responses in chatbot conversations, casting doubt on the nature of the interaction.

Reactive Measures: Responses Taken When Unmasking Chatbot

Deception

Upon realization of the fraudulent nature of the interactions,

individuals took a range of actions to safeguard themselves and

seek restitution. P11 and P12 resolutely distanced themselves by

blocking and erasing all traces of contact with the deceptive

entities. P9 and P10 adopted privacy-enhancing measures by

modifying settings and locking their social media accounts to

mitigate potential data breaches. The proactive involvement of

P10 and their friends in reporting the fraudulent account

showcases a collective effort to counter the deceptive scheme.

P16 undertook a determined pursuit for justice by leveraging

legal channels, leading to the identification of the fraudster

and the eventual recovery of funds. The prevalence of loss led

P14 to discard evidence and cease further pursuit, while P5

unveiled a widespread sentiment of financial loss that spurred

collective complaints. P1 embarked on multifaceted protection

measures, implementing two-step authentication for online

accounts and periodically changing passwords. P2 organized a

public campaign to amplify awareness and advocate for corrective

action from authorities, highlighting the resilience of those

affected. In summary, the responses revealed various strategies,

from digital safeguards to legal action, demonstrating the

determination of individuals to navigate the aftermath of

chatbot deception, emphasizing the complex nature of user

reactions and their attempts to seek redress.

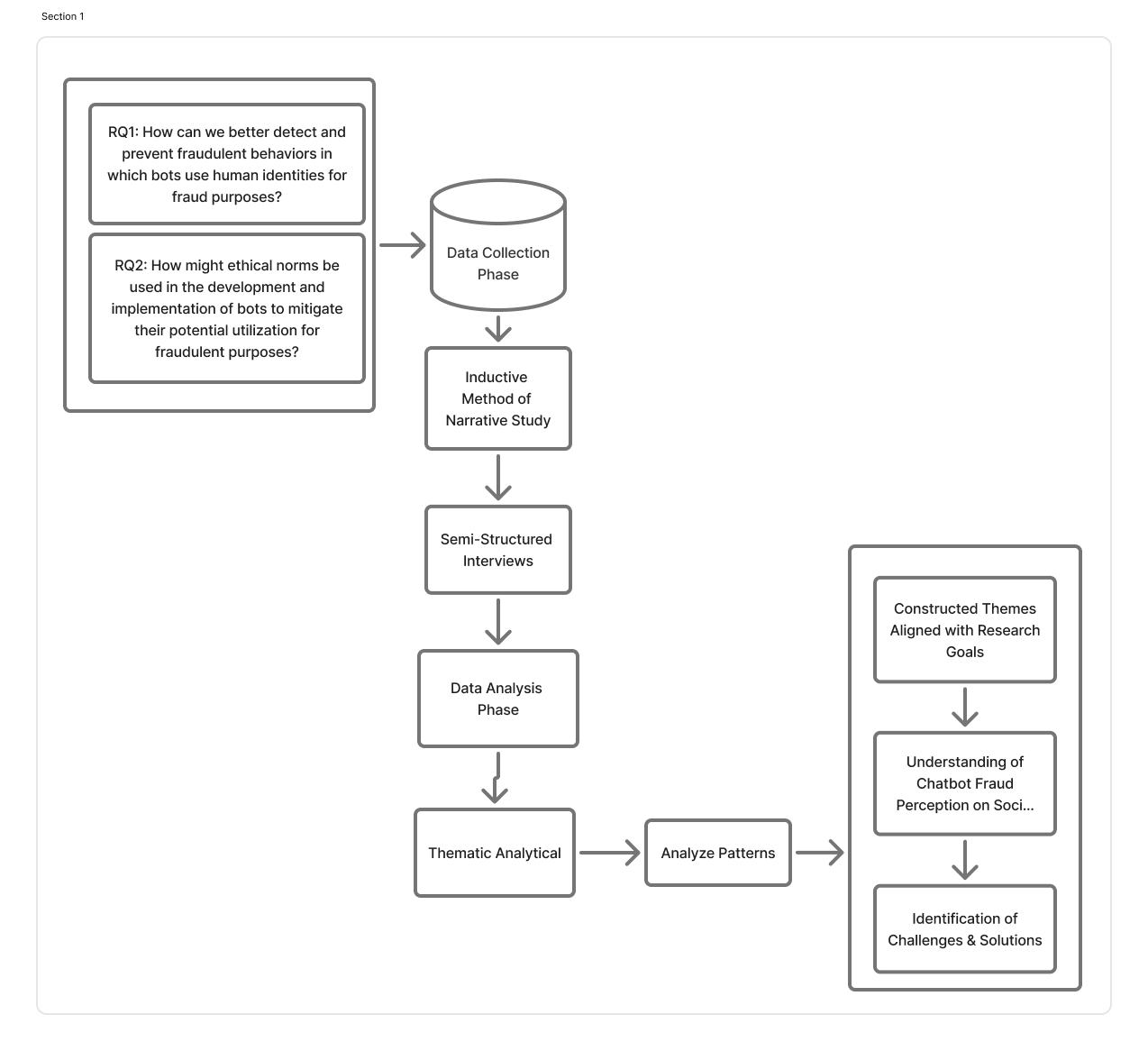

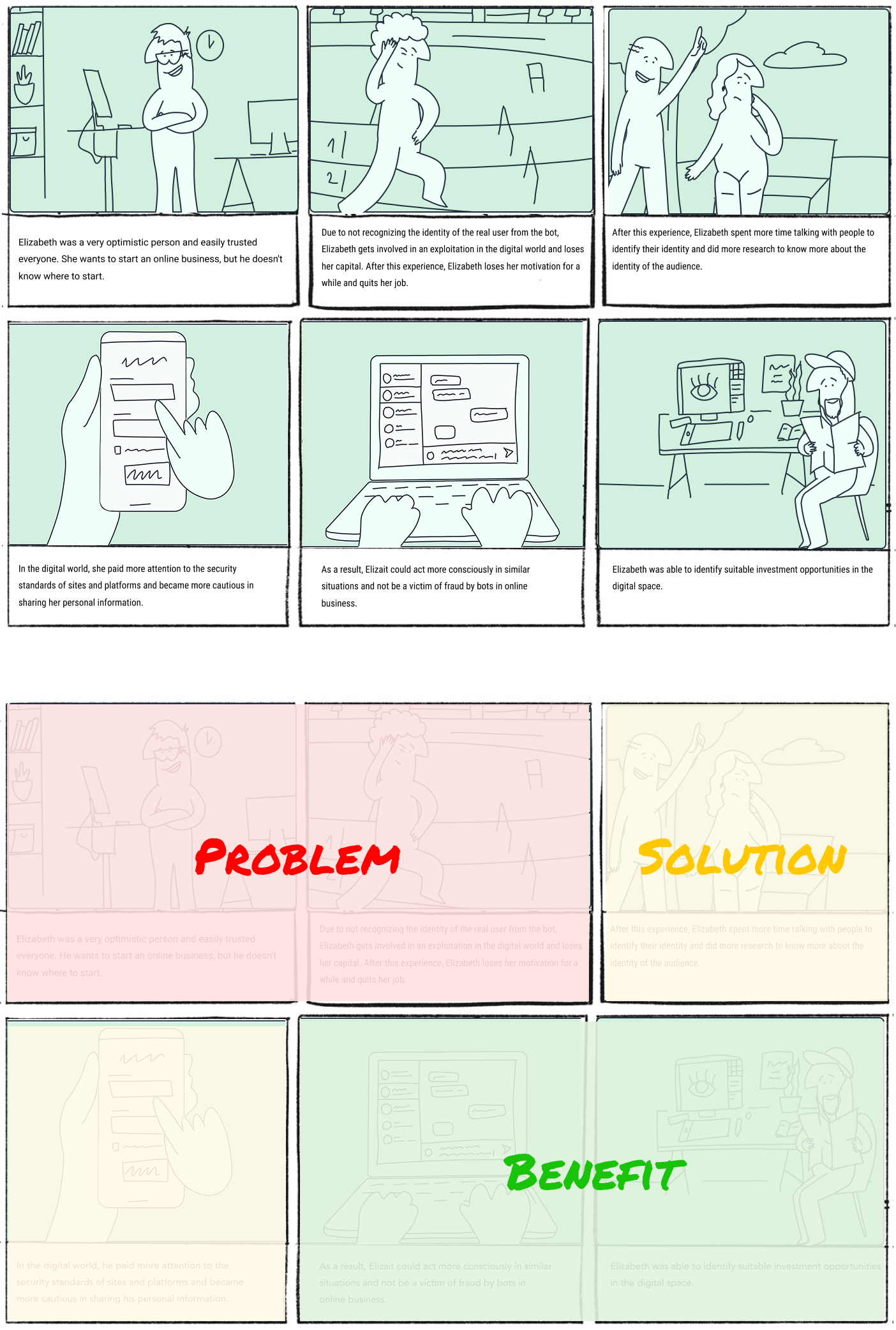

Story Board

Always try to structure it in a way that it starts with defining

a problem, followed by a solution to that problem, and benefits

achieved from that solution.

Fig 4. Research methodology and design prototyping framework

Design Prototyping

Always try to structure it in a way that it starts with defining

a problem, followed by a solution to that problem, and benefits

achieved from that solution.

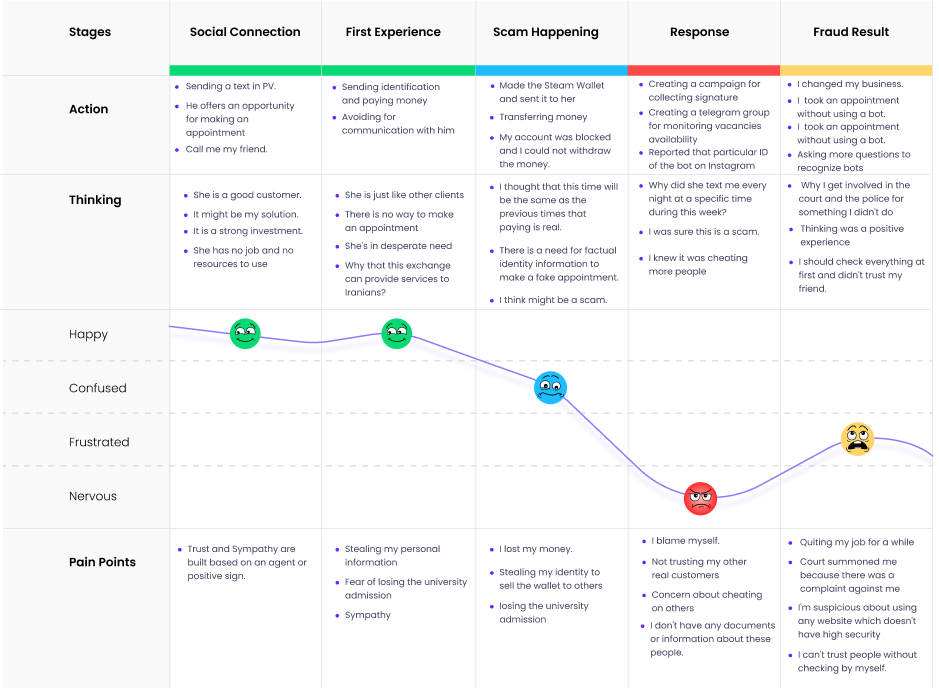

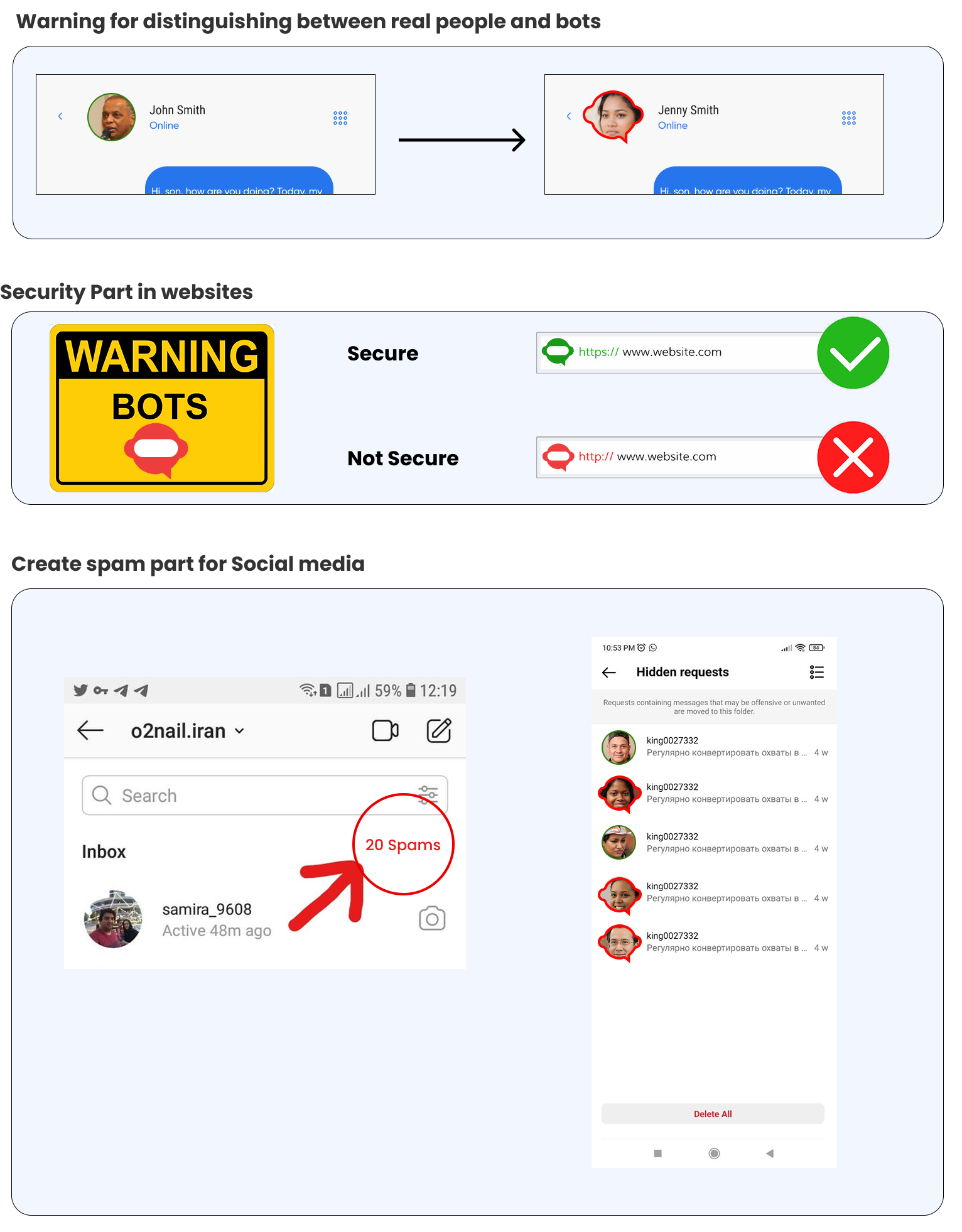

Guideline for recognizing bots before frauds

In the era of growing digital deception, it is imperative to

know how to identify chatbots before falling victim to them.

We propose a set of guidelines to help individuals identify

bots and protect themselves. Fig. 3 depicts a three-step

structure. This section focuses on the first stage of

research comprehension and preparation for the Pre-Attack

Phase. Our research indicates that in order to target

individuals, hackers first conduct research on various

factors, including Socio-Psych Analysis, Social Problem

Analysis, Information Gathering, Platform Selection, and

Targeted User. In the preparatory phase, they then

concentrate on Client Behaviour Analysis and Bot

Development. They attempt to target specific users and

provide comprehensive information using bots. Therefore,

vigilance stands as a paramount factor in the realm of

online security, driven by users' expectations for bots to

exhibit suboptimal performance or predictable behaviors.

Participants, particularly those who fell victim to

relationship and trust frauds (P4, P11, P6), have

underscored the critical necessity of cultivating skepticism

during online interactions with unfamiliar entities.

Suspicious behavior such as excessive flattery, a rush for

personal information, or inconsistencies in responses should

raise red flags. Coupled with this, participants who

experienced identity fraud (P9, P10, P2) underscore the

significance of verifying the identity of online contacts.

This can be achieved by cross-referencing information and

checking for unusual profile details. In line with this,

recent advancements in artificial intelligence and natural

language processing are making bots more human-like both

physically and emotionally, necessitating increased scrutiny

of online identities. This convergence aligns with the

recognition of the role of usability in the adoption of

security practices, encompassing software updates, password

management, and the utilization of unique passwords.

Additionally, participants' encounters with bot-driven prize

and grant frauds (P8, P15) suggest that one should be

cautious of unsolicited offers and free giveaways. It is

advisable to question the legitimacy of such claims and

verify their source before engaging.

Protection of Human Identity and Autonomy in Decision-making

During the second phase, referred to as the Attack Phase,

the perpetrators concentrate on cultivating and then

exploiting interpersonal connections. Initially, an

attempt is made to emulate human-like behavior and

articulate a request. Subsequently, throughout the course

of the connection, it is important to cultivate loyalty

and establish trust. Ultimately, the use of psychological

profiling of individuals via cultural manipulation is

employed to strategically target potential victims. While

chatbots have made strides, they have not attained

complete human-like behavior , aligning with participants'

experiences (P3, P5, P15) of chatbots seamlessly

transitioning between automated and human-like

interactions, concealing true intent, and manipulating

human psychology. Users should recognize chatbots'

limitations in mimicking human behavior and remain

vigilant. Kiel Long's insights into the prevalence of bots

on social media and the accessibility of bot creation

tools underscore the need for users to be attentive to

unusual behavioral patterns. Also, specific suspicious

behaviors identified by participants (P6, P13, P10, and

P14) include repetitive single-sentence responses and

immediate replies inconsistent with typical human

interactions, so users should be cautious when chatbots

provide inappropriate responses, such as repetitions,

out-of-context messages, ignored questions, or excessive

compliments. As also emphasized by Chaves, users should

exercise caution if chatbots engage in extended, which is

in line with the P11 remark, irrelevant small talk during

interactions. Additionally, bots may repetitively use

phrases, statements, or jokes, which can raise suspicion

during interactions. Researchers propose detecting bots

based on comment repetitiveness, underscoring the

significance of users noting chatbots that consistently

employ similar phrases or statements, characteristic of

automated responses.

Furthermore, Yixin Zou underscores the importance of caution when chatbots request sensitive information or engage in suspicious activities. As experienced by P10, users who perceive a loss of privacy control may become reluctant to further engage and could not potentially protect themselves from fraudulent activities. Immediate action in response to such suspicions is crucial. Implementing multi-pronged security measures, including two-factor authentication (2FA) and identity theft protection, can effectively mitigate fraud risks. Some chatbots, as highlighted by P15, attempt to manipulate human psychology by exploiting emotional connections and users' greed for quick monetary gains. Awareness of tactics involving emotional and financial manipulation, such as unwarranted requests for donations and false promises of substantial profits, empowers users to identify potentially fraudulent chatbot interactions. Additionally, general-purpose, emotionally aware chatbots are designed to discern users' interests and intents from conversation context. Users should exercise caution if chatbots exhibit excessively emotional or unnatural responses, as this may indicate a non-human entity. In summary, vigilance during interactions, awareness of chatbot limitations, recognition of suspicious behaviors, and the implementation of multi-pronged security measures are key guidelines for effectively recognizing and safeguarding against fraudulent chatbot interactions.

Furthermore, Yixin Zou underscores the importance of caution when chatbots request sensitive information or engage in suspicious activities. As experienced by P10, users who perceive a loss of privacy control may become reluctant to further engage and could not potentially protect themselves from fraudulent activities. Immediate action in response to such suspicions is crucial. Implementing multi-pronged security measures, including two-factor authentication (2FA) and identity theft protection, can effectively mitigate fraud risks. Some chatbots, as highlighted by P15, attempt to manipulate human psychology by exploiting emotional connections and users' greed for quick monetary gains. Awareness of tactics involving emotional and financial manipulation, such as unwarranted requests for donations and false promises of substantial profits, empowers users to identify potentially fraudulent chatbot interactions. Additionally, general-purpose, emotionally aware chatbots are designed to discern users' interests and intents from conversation context. Users should exercise caution if chatbots exhibit excessively emotional or unnatural responses, as this may indicate a non-human entity. In summary, vigilance during interactions, awareness of chatbot limitations, recognition of suspicious behaviors, and the implementation of multi-pronged security measures are key guidelines for effectively recognizing and safeguarding against fraudulent chatbot interactions.

Guideline for recognizing bots after frauds

In the attack masking, the scammer has covered traces by

deleting the account, changing Identity, and Changing the

technique. That is why in the Delaying level, the victim

blames himself and faces the consequences. In the context of

recognizing chatbots, several distinct patterns emerged

among our participants as they uncovered their interactions

with chatbots during or after fraudulent experiences. P11

and P14, notably, only came to the realization that they had

been interacting with chatbots after the fraudulent

incidents had concluded. In contrast, P4 and P10 discerned

that they were dealing with chatbots during the fraudulent

exchanges themselves. P14, P5, P6, and P16 initially

operated under the assumption that they were engaging with

genuine individuals, but as their interactions progressed,

they gradually became more convinced of chatbot involvement.

On the other hand, P12 and P3 expressed uncertainty about

whether their interactions were with humans or bots. Our

participants often found themselves in a state of ambiguity

following the occurrence of fraud. Interestingly, those with

a more technical background tended to exhibit higher levels

of suspicion. However, through discussions with various

participants, including individuals with expertise in

hacking, we were able to bolster participants' confidence in

distinguishing bot-driven interactions from genuine ones.

This uncertainty will likely be cleared up if these

participants follow the techniques and guidelines that we

have discussed in the previous sections of before and during

fraud. It is worth noting that some participants harbored a

reluctance to admit that they had been deceived by bots,

preferring to attribute the deception to human actors. This

preference arises from the complexity of chatbot behavior,

which, as observed by Zi Chu and colleagues, often is a

human account that is organized via the bot, giving rise to

the concept of "cyborgs" that interweave traits of both

humans and bots \cite{chu2010tweeting}. Hence, detecting the

presence of a bot in a fraudulent scenario, especially after

the fraud, can be exceedingly challenging. Therefore,

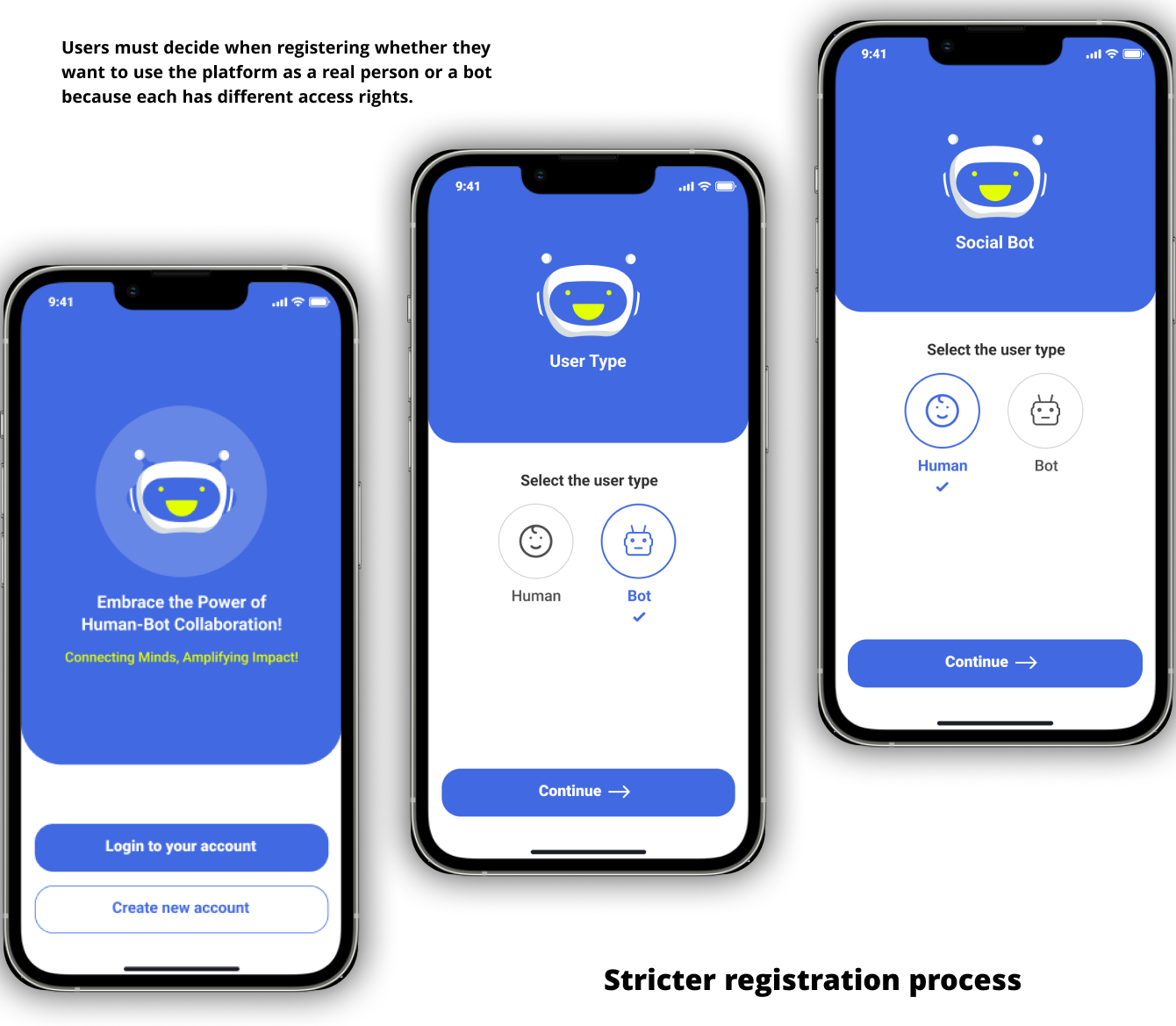

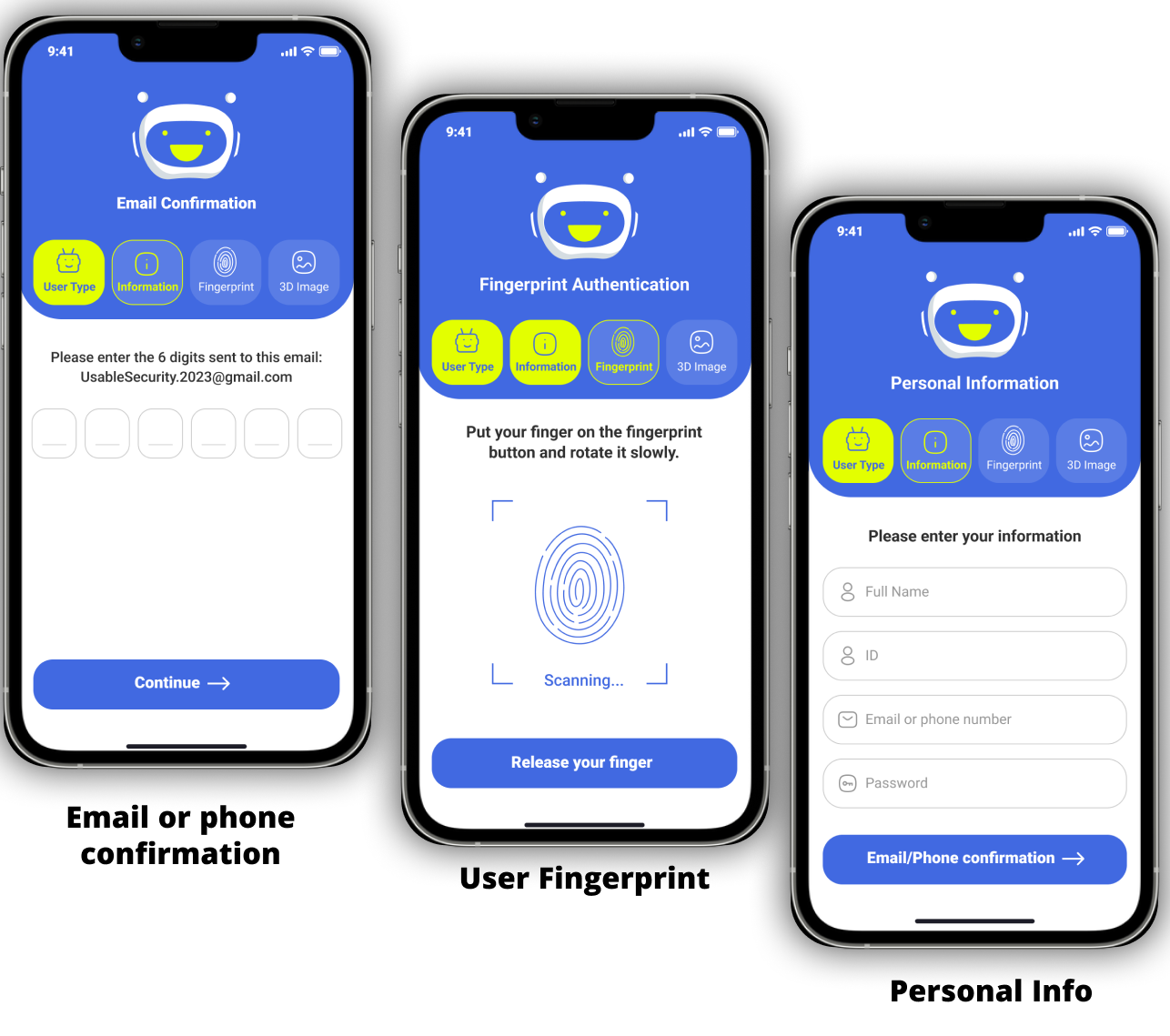

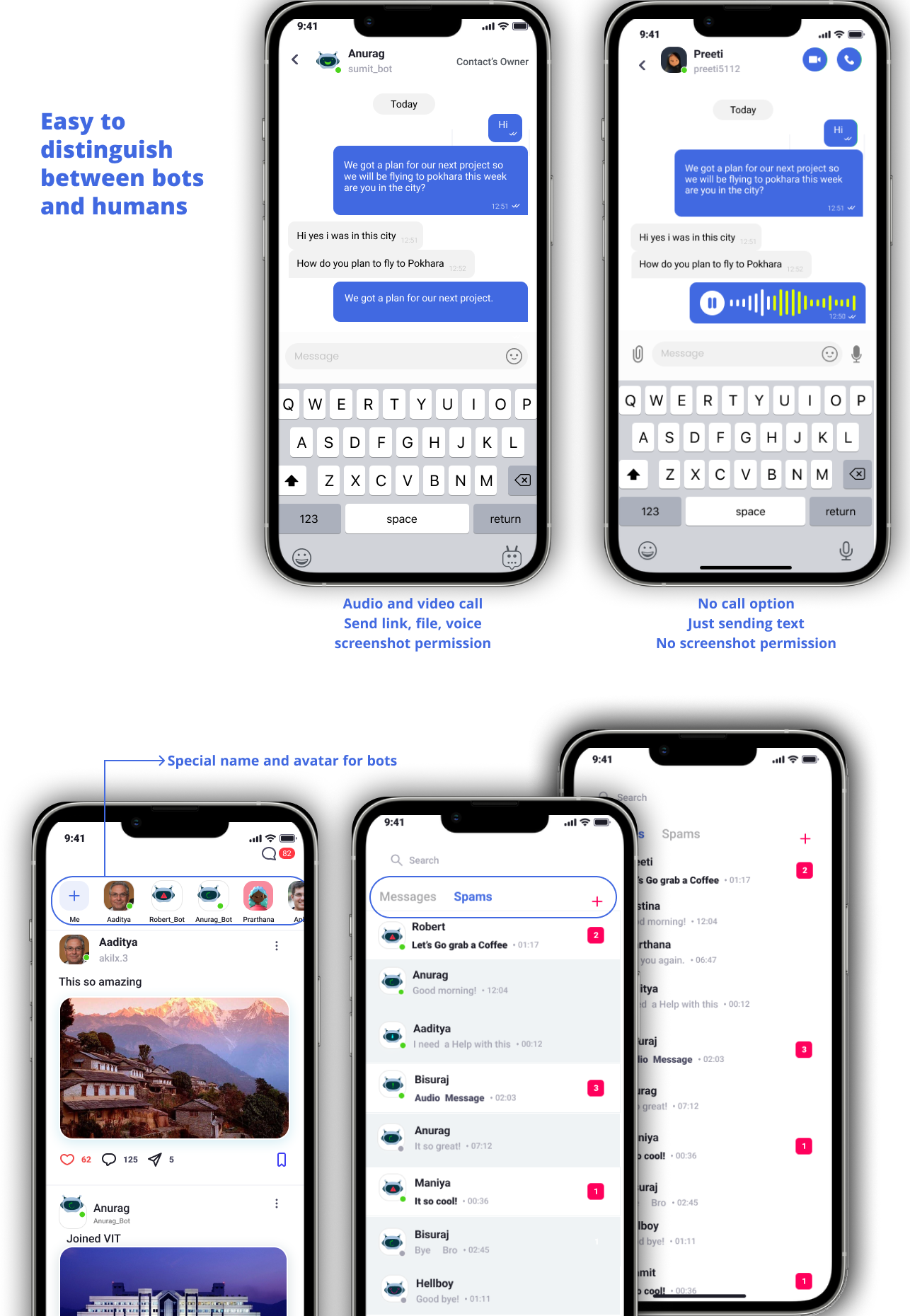

designing social media to recognize bots from humans will be

necessary. That is why, in this case, based on this study,

we designed our idea media secure.

Fig 5. Early SecureMedia concept and layout exploration

Persona

With the data collected from the interviews and survay, I

created a persona presenting an ideal of the application. The

persona helped me arrive at better solutions as it gave an

in-depth understanding of the user goals and frustrations and

the overall personality.

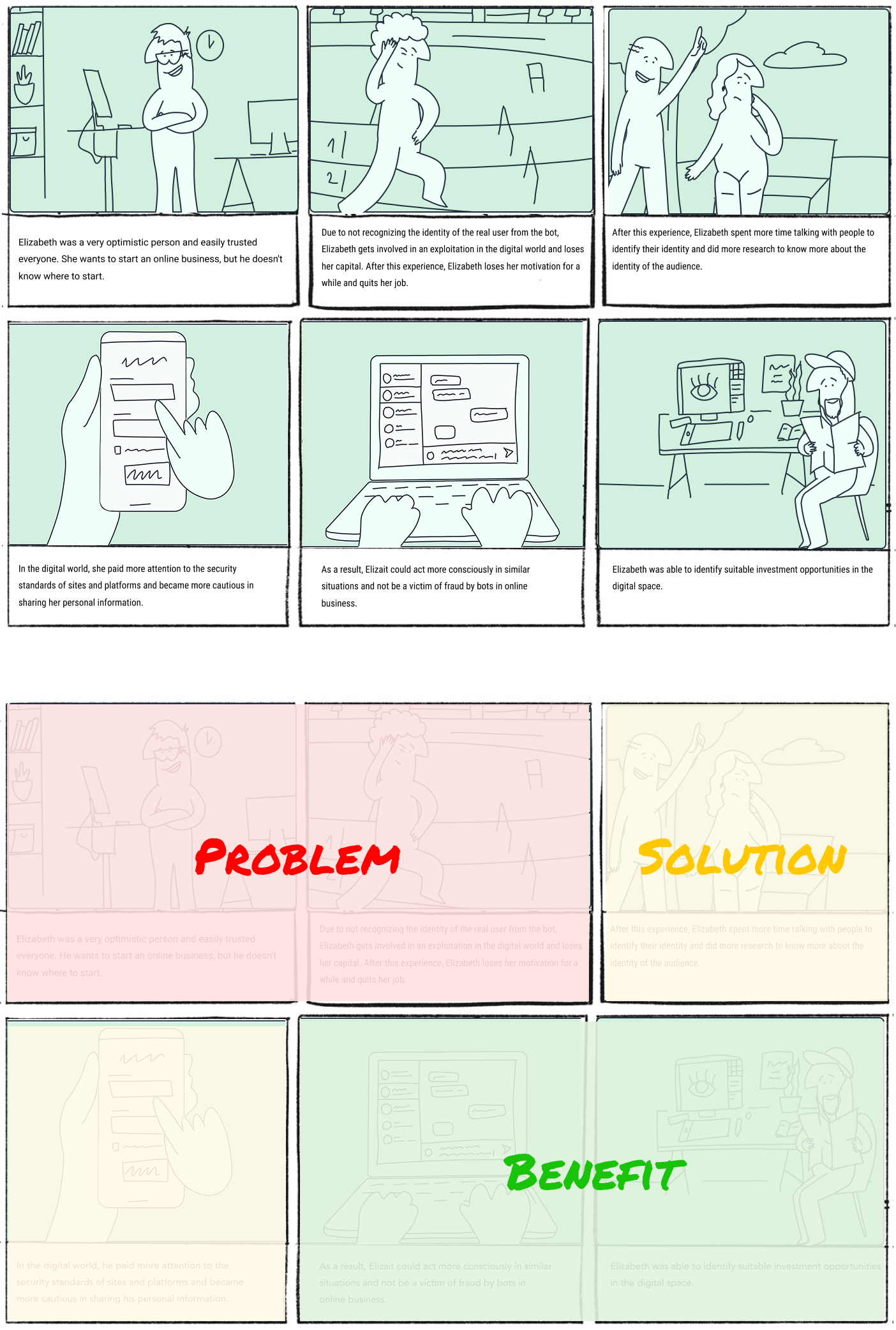

Journey Mapping

Fig 6. SecureMedia user persona

Fig 7. User journey mapping for fraud detection and prevention

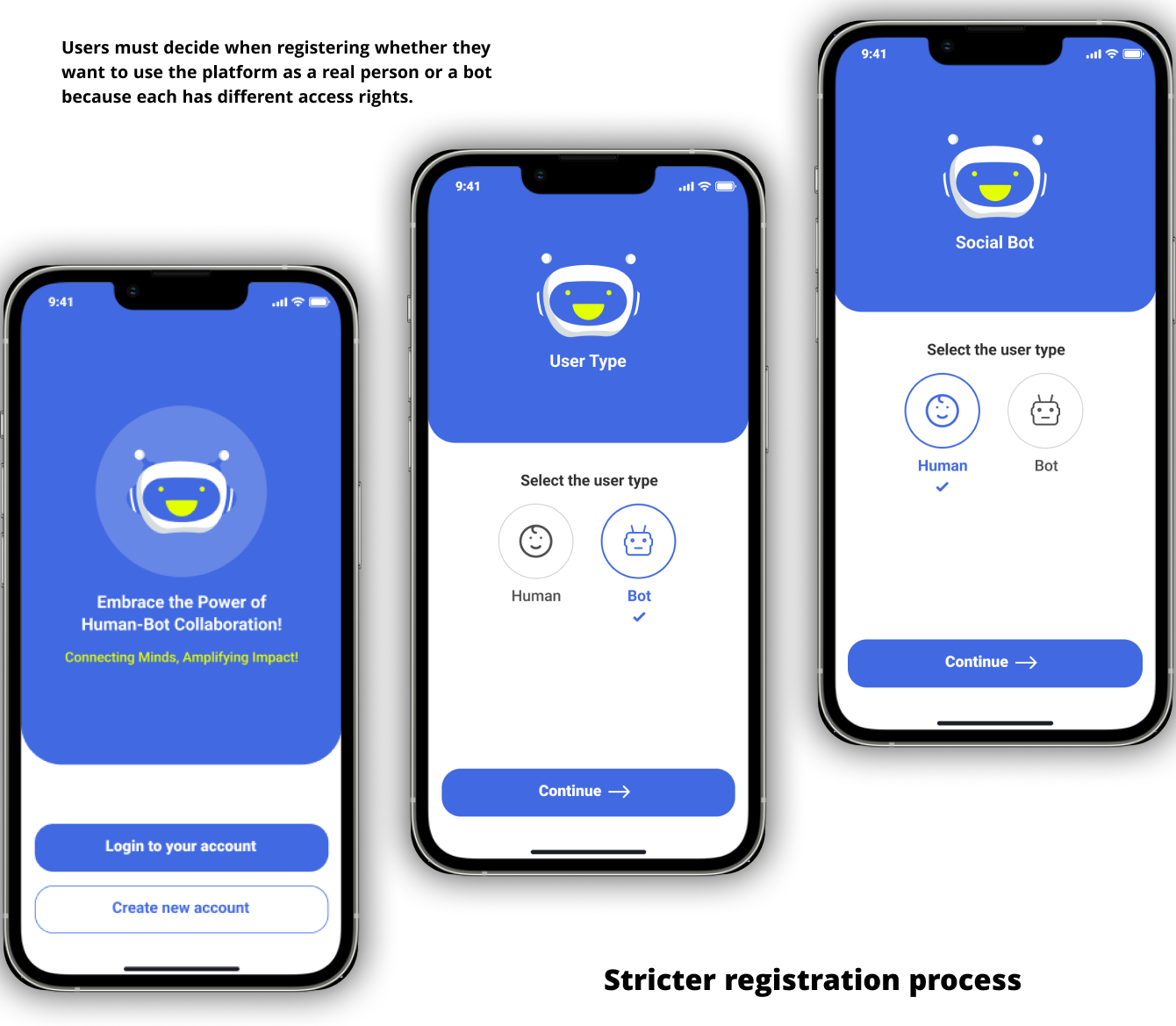

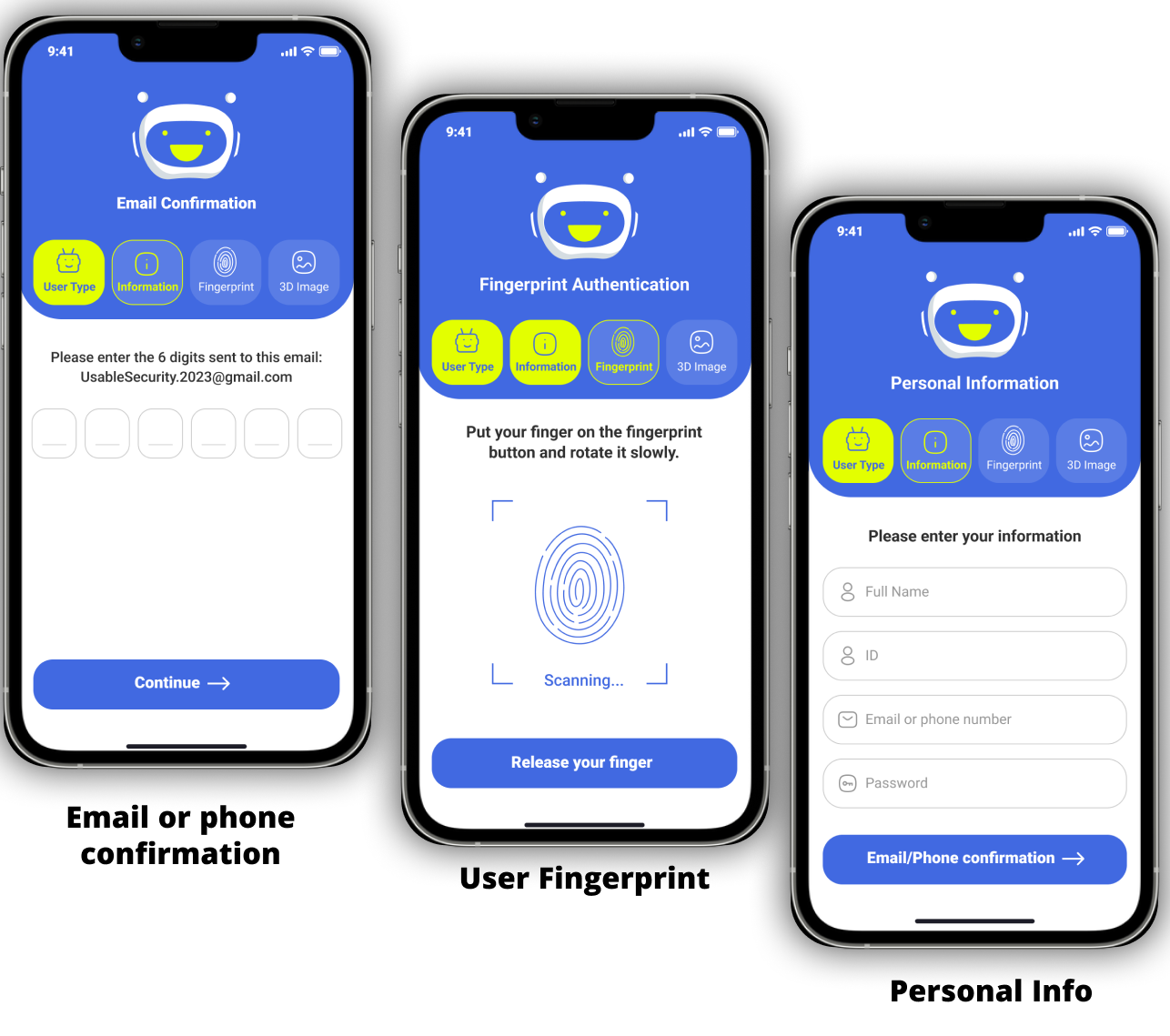

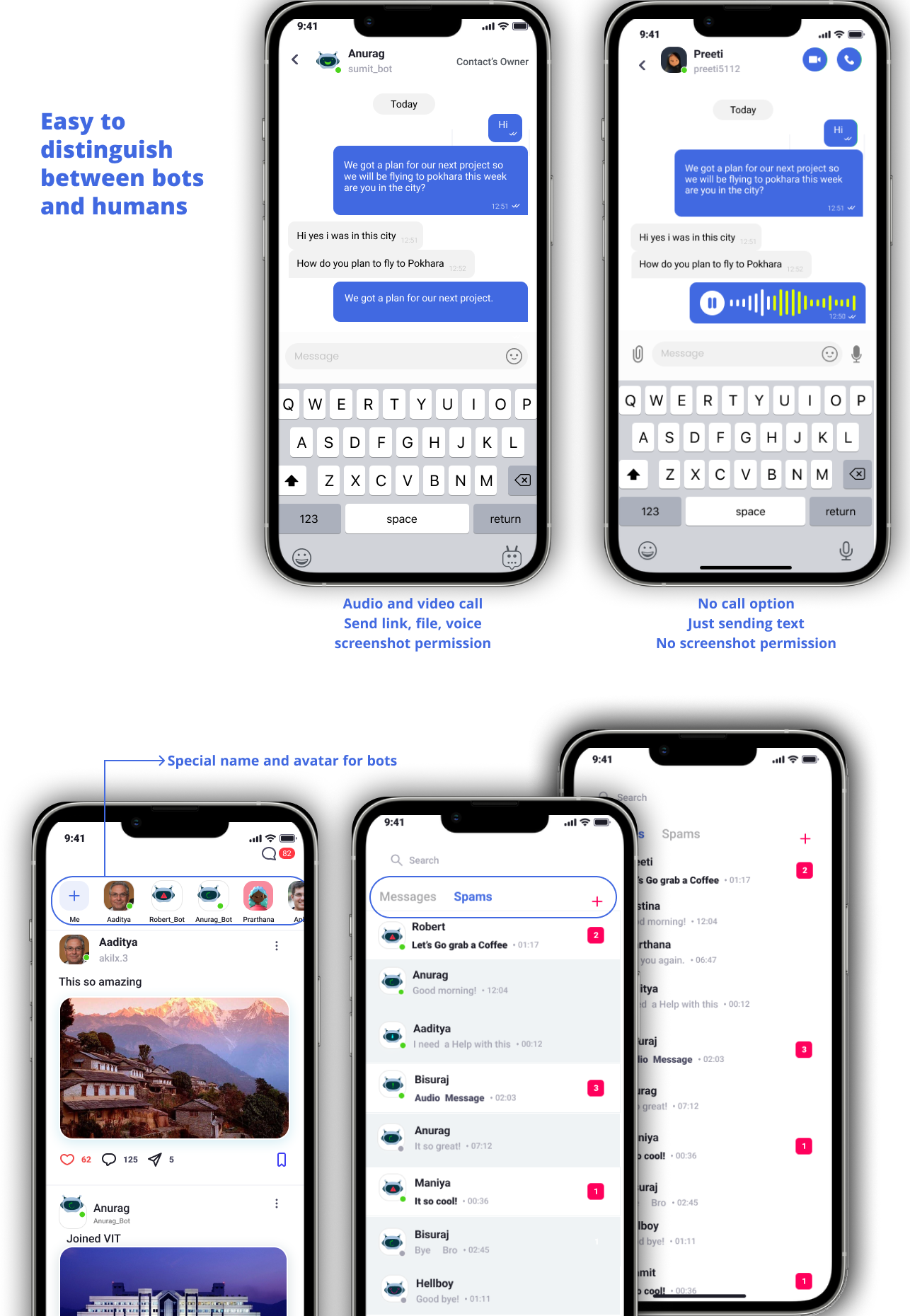

Fig 8. Interface design exploration and key screens

Fig 9. Interface design wireframe

Fig 10. Bot detection interface prototype

Fig 11. Complete user interface flow and interaction design

Fig 12. SecureMedia application final design mockup

SECURE MEDIA

,

Integrating Human and AI in Social Media, safely

It is an innovative idea to connect AI and humans in social media, which was published in the CHI

Conference as a short paper.

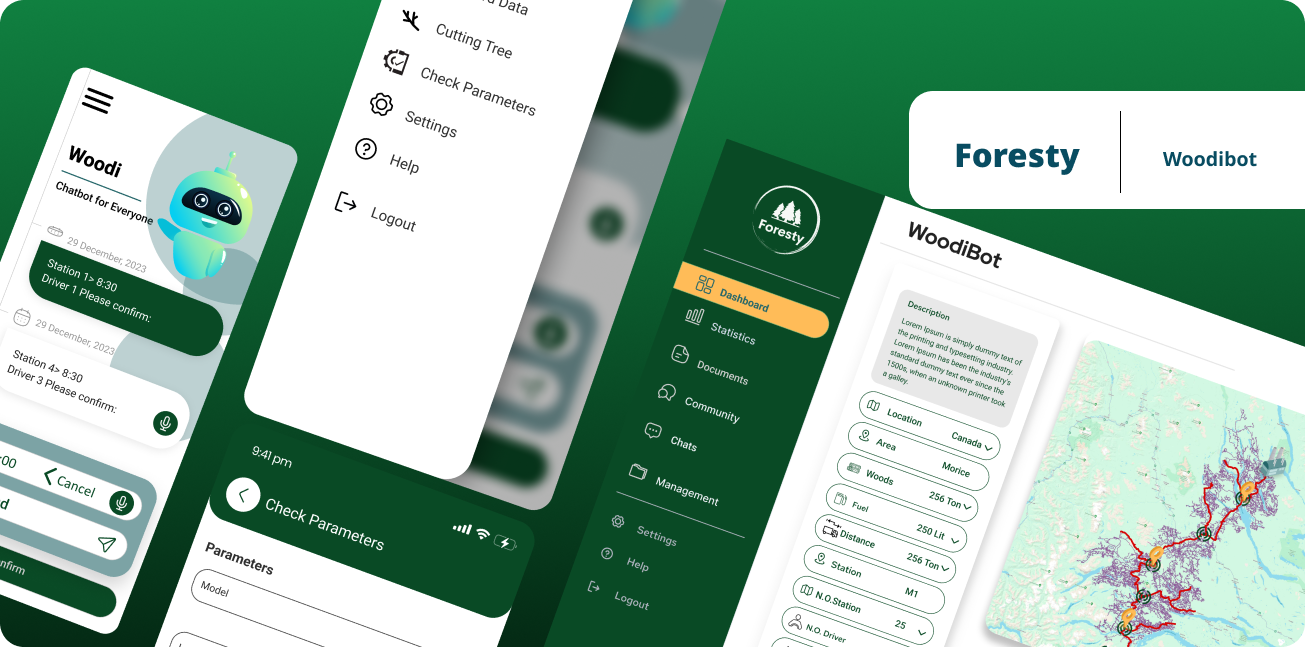

Design For Harvesting Woods in Forest: Forestry AI-Based System

It is an AI-based application empowered by Woody Bot, which is responsible for the connection between

users for harvesting wood in the Forest sustainably.

2024

SAFEMAP+ Earthquake Navigation

Academic Research

We're just into 2023 and we have big news! Our biggest design idea for finding safe routes during an

earthquake has been accepted for publication.

11th Jan 2023

RoboMind + A Game for finding career paths

2022

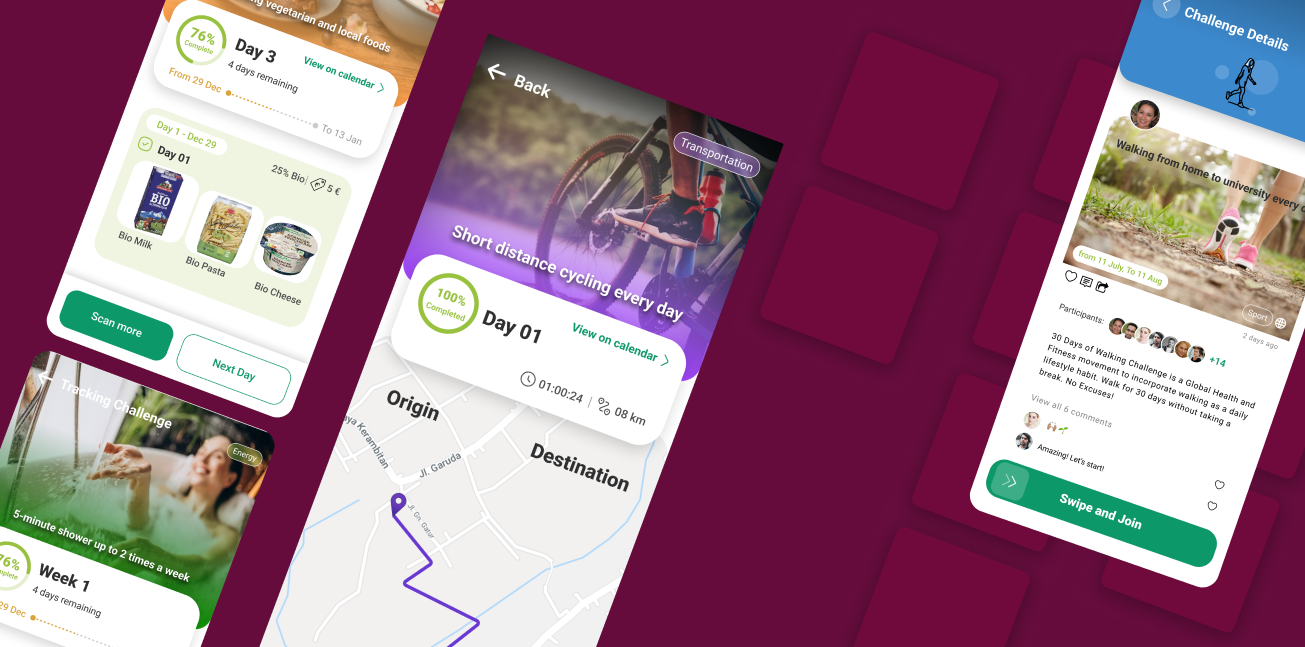

UI & UX DESIGN - Educational DIGITAL PRODUCT

CHALLENGE ACCEPTED! A Social Media for sharing environmental challenges with people.

2023

STRATEGY - PRODUCT DESIGN - dev